People in contact with the justice system

Jump to a section below

Key considerations

Over-representation of people with intellectual disability in the criminal justice system

People with intellectual disability are over-represented in the criminal justice system. A person who has come into contact with the criminal justice system may be a victim, witness or perpetrator of a crime. People with intellectual disability are over-represented in prisons and also have a higher risk of being a victim of crime compared to people without intellectual disability. Many people who are offenders are also victims of crime.

Intellectual disability is not always obvious when contact is made with the criminal justice system, meaning that appropriate adjustments and supports may not necessarily be provided. This may further contribute to the over-representation of people with intellectual disability in the criminal justice system.

People with mental illness are also over-represented in the criminal justice system

People with mental illness are also over-represented in the criminal justice system. This is concerning because people with intellectual disability are more likely to experience mental illness than people without intellectual disability. However, the majority of people with mental illness do not offend.

Key challenges in meeting the mental health needs of people with intellectual disability in contact with the criminal justice system

Although this section describes challenges in meeting the mental health needs of people with intellectual disability who have come into contact with the criminal justice system, sometimes contact with the justice system is the key time when services may become involved. Contact with the justice system may mean that supports are activated for the person, which may help to reduce reoffending.

Mental health problems in people with intellectual disability who have offended are often not evident until after contact has been made with the criminal justice system. Therefore, there are very few opportunities for primary prevention of offending behaviours, and it may be more difficult to prevent reoffending. There is currently no court diversion program in NSW specifically for people with intellectual disability* that would focus on providing mental health treatment to the person as an alternative to incarceration. Intellectual disability is also not always obvious when contact is made with the criminal justice system. This means that the person:

- may not receive mental health supports that are appropriate for them, or

- mental health supports/programs may be provided in a format that is not accessible to them.

*The Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network has a Court Liaison Service that provides mental health services in 22 NSW Local Courts. The service is not aimed at people with intellectual disability but people with co-occurring mental illness and intellectual disability are not excluded from the service.

Contact with police and the criminal justice system can be traumatising. Mental health needs often cannot be fully addressed or supported in the early stages of the person’s journey through the criminal justice system. People with intellectual disability may also have a mistrust of services and service providers. This could be due to past experiences, such as:

- service providers not listening to the person and instead speaking only to carers,

- not using trauma-informed care, and

- appearing frustrated about working with people with intellectual disability.

People with intellectual disability may also use services that are familiar to them and have a mistrust of new services when they are unable to access their familiar services. The loss of these familiar supports may also contribute to the trauma they experience within the criminal justice system.

A research report commissioned by the Disability Royal Commission on police responses to people with disability was released in October 2021 and may be of interest to you for further reading.

For people with intellectual disability, transition out of prison may not be optimal. The post-release period is often a high-risk period for people with mental illness and can often result in breakdowns in the continuation of care, relapse of mental illness or reoffending. It can be difficult for those with no post-release conditions to access post-release transition and reintegration programs, with many people relying on non-government organisations, such as the Community Restorative Centre, to provide these programs. However, not all programs are accessible to people with intellectual disability.

For those with post-release conditions, compliance with seeing a mental health professional can often be low due to the person not understanding the benefits of mental health care, the prioritisation of other post-release services and programs over mental health, and reincarceration or re-engagement with alcohol or drug use.

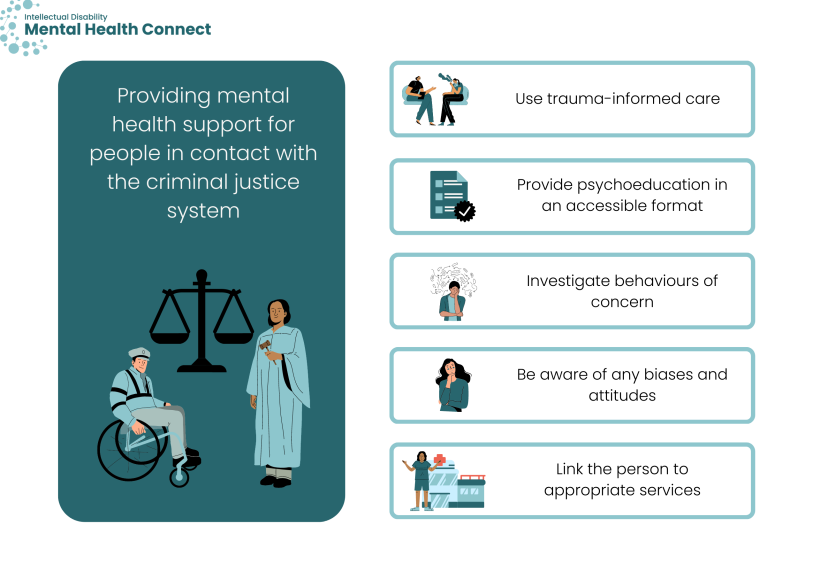

How I can meet the mental health needs of people with intellectual disability in contact with the criminal justice system

Mental health professionals working in mainstream settings typically do not provide services to the person while they are in prison or in remand. People in prison are not able to access Medicare or the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (medications in custody are funded by the State). Their health needs are largely managed by the Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network and psychologists employed by Corrective Services NSW. There is the potential for mainstream providers to work alongside prison providers while the person is in custody but the mainstream provider would need to be funded by the person in custody.

Mainstream professionals may more typically provide mental health services in line with post-release conditions or other correctional programs. This is an important role as post-release mental health treatments can reduce rates of reoffending. [1, 2] Mainstream professionals can also link in with people in custody prior to their release and, therefore, provide continuity of care when the person is released.

Use trauma-informed care

Professionals may provide mental health services to people with intellectual disability who have previously had contact with the criminal justice system. It is important to use a trauma-informed approach or link the person with a trained trauma therapy clinician. Recognise any trauma that may be associated with the incarceration of family members or other negative past experiences like abuse and neglect, including any trauma that the person may have experienced during their previous contact with the justice system. For example, this could involve investigating any past experiences of sexual trauma that may be leading the person to be a perpetrator of sexual assault and other crimes. Professionals should also recognise any intergenerational trauma that the person may be experiencing and take a nuanced cultural approach.

There is more information about trauma-informed care here and people who have experienced trauma here.

Provide psychoeducation in an accessible format

Professionals could also provide accessible psychoeducation to the person with intellectual disability, particularly in relation to the effects of substance use and/or abuse. The psychoeducation should ideally focus on information that is about, or relevant to, people with intellectual disability. A translation of psychoeducation for the general population into an accessible format is not enough.

The Council for Intellectual Disability has a series of health guides about people with intellectual disability, including a factsheet on Alcohol and Other Drugs. You could adapt some of this information into Easy Read factsheets for people with intellectual disability. For information on how to create your own Easy Read information, see the Communication section. Many people with intellectual disability will still require support to use Easy Read information.

Investigate behaviours of concern

Behaviours of concern, including self-harm, violence and other offending behaviour, may be communicative in intent and directly related to the person’s health, mental health or support needs. It is important to investigate all behaviours of concern and ensure that there is a management plan in place for these behaviours.

It is also important that there are interventions in place immediately on release, as this is a particularly high-risk time for suicide and self-harm. The risk of accidental overdose or adverse reactions immediately after release is also increased, particularly if the person has not been using drugs in prison (or has been using smaller quantities). Professionals need to be aware of these risks.

Be aware of any biases and attitudes

Be aware of any biases or attitudes towards people with intellectual disability who have had contact with the criminal justice system and how these attitudes may be affecting service provision. In some cases, certain behaviours of people with intellectual disability can be misinterpreted.

Link the person with appropriate services

It is important for all professionals to link the person with appropriate services, particularly during pre-release planning. It is crucial that the person continues to receive supports and services after release from custody, and that professionals continue to refer the person to appropriate services.

Mental health professionals can link the person to a range of different services, including disability support services. If the person is not accessing NDIS supports, it is important to find out if they would be eligible for support. The person can be referred to the Justice Advocacy Service if they require legal advice immediately or in the future. The Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network’s Mental Health Helpline and the Community Restorative Centre can also provide advice to the person post-release.

Disability and health service providers also have an important role in linking the person to appropriate services and supporting them at different stages. For example, disability professionals can help to facilitate meetings with lawyers who may not have experience working with people with intellectual disability.

Useful programs and services

- The Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network is running the Community Transitions Trial – a program that applies a person-centred, prison in-reach model of care to support the community reintegration of vulnerable patients under the care of the Custodial Mental Health Service. The service is not aimed at people with intellectual disability, but people with co-occurring mental illness and intellectual disability are included.

- Corrective Services NSW has a Coordinated Continuous Model of Care, which provides linkages to Local Health Districts for people exiting custody with a history of psychosis.

When it comes to supporting a person with intellectual disability who has come into contact with the criminal justice system, there is often multi-agency involvement with no agency taking a lead role. Furthermore, there are often many assessments conducted, but the recommendations from these assessments are not implemented. Mental health professionals can take a lead role in reviewing mental health assessments and ensuring that recommendations are implemented before new assessments are conducted. If the person has an NDIS plan, mental health professionals can ask the person for their plan and assist in coordinating this plan so that the person is able to access all funded services.

Ensure that there is someone who can coordinate all the person’s support and provide appropriate throughcare (e.g. ensuring the person has transport to get to post-release mental health, health and disability support appointments).

Useful programs and services

- All incarcerated people in Corrective Services NSW with three or more months to serve have a case manager. The case manager assists with co-developing case plans including mapping a person’s journey while in custody and after release. Case plans do not only focus on offending behaviours and programs, but also on post-release planning and linking incarcerated people with supports once they are released. Professionals and non-government organisations work together to provide continuity of care to the community. If a person has a community order, a community corrections case officer uses the case plan to further case management once the person is released from custody.

- Corrective Services NSW’s Service and Programs Officers may also assist with ensuring successful reintegration of offenders back into the community. They work closely with case managers to implement the case plans.

- The Community Safety Program works with people who have a high risk of reoffending and who have intellectual disability. They are generally a tertiary service that consults with service providers, assists with transition from custody to community, and develops workforce capacity to work with this complex cohort. They also provide case management to forensic patients under the Mental Health Review Tribunal.

It is important to be aware of the increased risk of contact with the criminal justice system and common risk factors in people with intellectual disability (a list is provided in the additional background information below). This can help with early identification of those who may be at risk.

All professionals can participate in planning how the person’s housing, financial, and daily support needs can be met to reduce risk of offending. Planning can also help reduce re-offending, as some people may prefer to stay in prison because there is safe accommodation, a strict schedule, and the opportunity to have jobs in prison. It is also important to plan for transitions and help the person with intellectual disability with their mental health needs as they navigate these transitions. 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education has an e-learning course for disability professionals on how to provide mental health support to a person with intellectual disability through transitions and life events. The course is available for a small fee. Professionals can also help to promote and encourage the acceptance of health and disability services.

Professionals can use strengths-based and other approaches to reduce contact or further contact with the criminal justice system. For example, some strategies may include:

- engaging the person in opportunities and activities where they can experience success

- engaging the person in opportunities and activities where they can experience a sense of belonging

- engaging the person in activities that may enhance quality of life

- engaging the person to take on achievable responsibilities

- helping the person to improve social skills, coping skills, emotion regulation, problem solving skills

- improving family relationships and dynamics.

Key resources

- Justice Advocacy Service (run by the Intellectual Disability Rights Service) is available across NSW and is free. They are available for general legal help and to provide support throughout criminal proceedings. Someone from the Justice Advocacy Service can act as the “support person” for the person with intellectual disability. The Justice Advocacy Service can help regardless of whether the person with intellectual disability is a victim, witness or suspect. A volunteer from the Justice Advocacy Service can help the person to:

- know what to expect

- fill in paperwork

- understand their rights

- stay calm

- get legal advice

- understand what has happened or what will happen next.

- Corrective Services NSW’s Statewide Disability Services can address the disability support needs of people with intellectual disability in prisons. They assist with pre-release planning, including referral to the NDIS and other service providers. Statewide Disability Services has developed a list of programs that help with reducing offending, and also provides staff training in disability, behaviour support and communication.

- Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network’s Mental Health Helpline is free and available 24/7 on 1800 222 472. It is operated by mental health nurses and available to adults in correctional centres, adolescent detainees, their relatives and carers. The helpline is also available to staff of Justice Health, Corrective Services NSW and other Local Health Districts. Custodial Mental Health services deliver mental health care and treatment to people in custody across NSW correctional centres.

- Community Restorative Centre has a free telephone information and referral service. You can contact their telephone service on (02) 9288 8700 between 9am and 5pm, Monday to Friday. They also provide a range of throughcare, post-release and reintegration services and programs.

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education provides online learning courses to health and mental health professionals, disability professionals and carers on intellectual disability mental health. They have a course for disability professionals on how to support a person with intellectual disability who has come into contact with the criminal justice system.

Additional background information

About 4.3% of adults in Australian prisons have an intellectual disability. [3] However, intellectual disability is often not diagnosed or identified, meaning that the prevalence of intellectual disability in prisons could be higher. Without being identified as having intellectual disability, people with intellectual disability in prisons may not receive appropriate supports and their rights may not be upheld.

Offenders who are First Nations peoples are more likely to have intellectual disability than those who are not First Nations peoples. [4, 5] Other common characteristics of people with intellectual disability in prisons include:

- being young and male [4-6]

- having a history of psychosocial disadvantage [7]

- having a history of abuse and neglect [8]

- being unemployed [4]

- engaging in illicit drug use or substance abuse [7]

- having mental health needs or a personality disorder. [9]

Having a mental illness is associated with a higher risk of offending, and people with intellectual disability are more likely to experience mental illness than people without intellectual disability. The likelihood of a co-occurring mental illness among people with intellectual disability in prisons is 52.2%, compared to 41% among people without intellectual disability in prisons. [10] People with intellectual disability and co-occurring mental illness are also more likely to reoffend.

Compared to people without intellectual disability, people with intellectual disability are more likely to commit offences again and go back to prison. [11] This is likely because people with intellectual disability do not have the support they need when they leave prison. They may not have a job, a place to live, prosocial friends or adequate supports.

- Held M, Brown C, Frost L, Hickey J, Buck D. Integrated primary and behavioral health care in patient-centred medical homes for jail releasees with mental illness. Criminal Justice and Behaviour. 2012;39:533-51.

- Norton E, Yoon J, Domino M, Morrissey J. Transitions between the public mental health system and jail for persons with severe mental illness: a Markov analysis. Health Econ. 2006;15(7):719-33.

- Trofimovs J, Dowse L, Srasuebkul P, Trollor JN. Using linked administrative data to determine the prevalence of intellectual disability in adult prison in New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2021;65(6):589-600.

- Bhandari A, van Dooren K, Eastgate G, Lennox N, Kinner SA. Comparison of social circumstances, substance use and substance-related harm in soon-to-be-released prisoners with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2015;59(6):571-9.

- Haysom L, Indig D, Moore E, Gaskin C. Intellectual disability in young people in custody in New South Wales, Australia - prevalence and markers. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2014;58(11):1004-14.

- Emerson E. Poverty and people with intellectual disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(2):107-13.

- Devapriam J, Alexander RT. Tiered model of learning disability forensic service provision. Journal of Learning Disabilities and Offending Behaviour. 2012;3(4):175-85.

- Lunsky Y, Gracey C, Koegl C, Bradley E, Durbin J, Raina PJP. The clinical profile and service needs of psychiatric inpatients with intellectual disabilities and forensic involvement. Psychology, Crime & Law. 2011;17(1):9-23.

- Winter N, Holland AJ, Collins S. Factors predisposing to suspected offending by adults with self-reported learning disabilities. Psychol Med. 1997;27(3):595-607.

- Dias S, Ware RS, Kinner SA, Lennox NG. Co-occurring mental disorder and intellectual disability in a large sample of Australian prisoners. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47(10):938-44.

- Moore E, Indig D, Haysom L. Traumatic brain injury, mental health, substance use, and offending among incarcerated young people. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(3):239-47.