First Nations peoples

Jump to a section below

This section provides information predominantly for people in NSW. We acknowledge that all First Nations peoples are different and that the information may not apply to people in all parts of Australia.

Key considerations

Higher prevalence of intellectual disability compared to non-First Nations peoples

There is a higher prevalence of intellectual disability among First Nations peoples compared to non-First Nations peoples. The 2018 Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers found that 10.1% of First Nations males and 5.9% of First Nations females reported having an intellectual disability. [1] As the survey was only conducted with First Nations peoples living in households and excluded those living in remote communities, the prevalence may be higher than what is reported. The estimated prevalence of intellectual disability in all Australians is 1-2%. [2, 3]

Poorer mental health outcomes

First Nations peoples are 2.3 times more likely to report ‘high or very high’ levels of psychological distress compared to non-First Nations peoples. [4] Although there is limited data on mental health outcomes or comorbidity in First Nations peoples with intellectual disability, First Nations peoples are more likely to be admitted to hospital for mental health care and have more contacts with community mental health services than other Australians. [5] First Nations peoples also have higher mortality rates while in contact with mental health services, and higher rates of hospitalisation due to self-harm. [6, 7]

Multiple layers of disadvantage

First Nations peoples with intellectual disability often have multiple and complex needs, as health demands occur against a backdrop of:

- marginalisation

- discrimination

- disadvantage

- intergenerational trauma

- family and cultural breakdown

- unemployment

- poorer educational opportunities.

These experiences may influence their:

- help-seeking behaviour

- access to support and health services

- exposure to risk factors such as increased contact with the criminal justice system

- ability to have their needs met in mainstream service and care settings.

Key challenges in meeting the mental health needs of First Nations peoples with intellectual disability

Seeking help early is important for meeting mental health needs. First Nations peoples may be more reluctant to seek help for their disability or mental health needs. For example, someone may not seek help from a government disability service because they associate the service with the ‘welfare’ responsible for removing a family member in the past. Intergenerational trauma established from the Stolen Generations may also impact First Nations peoples’ willingness to seek help. To learn more about the impact of the Stolen Generations, see the Australian Human Rights Commission's Bringing them Home report.

First Nations peoples are more likely to be exposed to risk factors for poor mental health than non-First Nations peoples. These risks can include, but are not limited to:

- smoking, drinking alcohol, and taking other drugs

- experiencing negative self-esteem and self-worth, stress, and negative emotional reactions

- disengaging from healthy activities such as exercise, healthy sleeping patterns, and taking medications

- injury

- experiencing trauma. We have more information about trauma here

- homelessness

- contact with the criminal justice system. You can read more about First Nations peoples’ contact with the criminal justice system in the additional background information below. There is also information about meeting the mental health needs of people who have come into contact with the criminal justice system here.

Each First Nations community and person within the community is different. Some communities may have different views and beliefs about mental health, disability, and interpretations of behavioural changes. Culture and intergenerational trauma caused by poverty and marginalisation may contribute to some of the views and beliefs.

First Nations peoples’ mental health is often considered in terms of social and emotional wellbeing. Social and emotional wellbeing recognises the importance of harmonised interrelations between the social, political, and historical domains of an individual’s life, and may be supported through connection to:

- culture

- community

- family and kinship

- mind and emotions

- body

- spirit, spirituality, and ancestors.

For more information about social and emotional wellbeing, see this page by the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

These different views and beliefs can influence whether an individual seeks out mental health care, and subsequently their experience of and response to the mental health care.

Culturally safe care is critical to meeting the mental health needs of First Nations peoples. Culturally safe care acknowledges and is informed by First Nations peoples’ multi-dimensional cultural and spiritual structures. It includes an understanding of power differentials and the impact of racism at an individual and institutional level on peoples’ wellbeing. Culturally safe care aims to make a person feel accepted and safe. [8] Mainstream mental health care may not adequately meet the cultural needs of First Nations peoples with intellectual disability.

For example, some First Nations peoples may:

- dislike one-on-one approaches that are common in mental health care

- reject direct approaches from strangers and consider it rude to be asked numerous questions

- find it inappropriate to talk to strangers about their innermost thoughts and feelings, especially when often the person conducting assessments and treatments is not a First Nations person

- experience the voices of their deceased relatives as an appropriate cultural response to grief, which may be misinterpreted as a hallucination by an uninformed mental health professional

- have low English literacy and differing concepts of numbers, time, and space, which are important for standard cognitive tests used for diagnostic purposes.

How I can meet the mental health needs of First Nations peoples with intellectual disability

Meeting the mental health needs of First Nations peoples with intellectual disability requires the provision of holistic and empowering care and support by adapting your practice to be culturally safe. Cultural safety seeks to achieve better care by being aware of differences, considering power relationships, adopting a reflective approach, and allowing the person to determine whether mental health care is safe. [9]

It is important to use trauma-informed care and routinely include culturally safe screening for trauma in your practice. You can read more about trauma-informed care here.

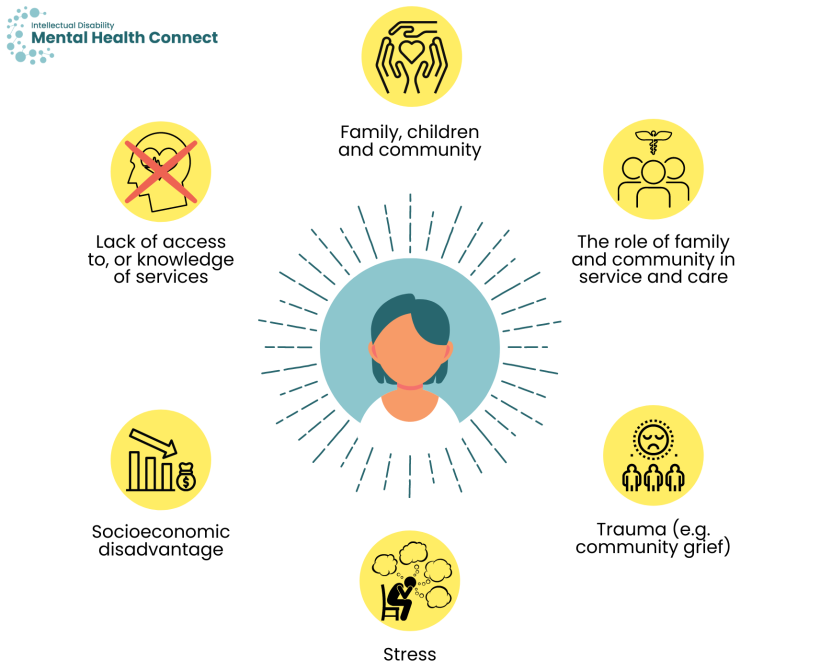

You may also want to consider the person’s traditions and attitudes relating to:

- family, children and community

- the role of family and community members in service and care (involvement of broader community members is more common for First Nations peoples)

- trauma such as community grief (when the community is collectively affected by trauma)

- stress

- socioeconomic disadvantage

- lack of access to, or knowledge of, services.

Cultural competency describes the ability of individuals and services to work or respond effectively across cultures and provide culturally safe care.

Campinha-Bacote proposes a culturally competent model of care for health care services that can easily be remembered through the acronym ASKED. The components of the model include [10]:

- Awareness of your own biases and culturally appropriate attitudes and actions

- Skills to assess your cultural competency level and to conduct a cultural assessment sensitively

- Knowledge of cultural practices and values, worldviews and beliefs

- Encounters with people from specific First Nations communities

- Desire to become culturally competent.

You can build your cultural competency by engaging in training. Some examples of training programs are provided below.

Services and training programs that can support improvement of your cultural competency

- AIATSIS’s Core cultural learning is an online course with 10 interactive modules.

- Centre for Cultural Competence Australia has an online cultural competency course. They also provide consulting services.

- Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association has training designed for doctors, nurses, health care workers, students, government organisations and universities.

- Mirri Mirri offers programs and professional workshops for individuals and organisations. They also offer culturally-focused services for organisations aimed at developing relationships and engagement with First Nations communities.

- BlackCard delivers cultural education workshops, training, and consultancy.

You can also build your cultural competency by getting involved in your local or relevant First Nations community. Seek out the people who are practising or who are helping with the revival of the culture in those communities. You can also investigate whether you can attend a yarning circle with the person with intellectual disability and their family (if they are comfortable with this). ‘Yarning’ is the First Nations cultural form of conversation intended to build trust and relationships.

Psychological assessment tools used for the general population have limited applicability to First Nations peoples. Assessments for First Nations peoples should be culturally safe and informed, as well as scientifically and biomedically valid.

Mental health professionals can utilise the following diagnostic and assessment tools that have been created or modified for the assessment and treatment of First Nations peoples.

Culturally appropriate assessment tools for First Nations peoples

Guddi Way screen (The Guddi Protocol for Adults)

The Guddi Protocol consists of culturally safe questions relating to thinking skills, psychosocial functioning, depression, psychosis, and post-traumatic stress disorder. For more information see here.

IRIS (Indigenous Risk Impact Screen) Screening Instrument and Risk Card

IRIS Screening Instrument and Risk Card is a culturally appropriate screening and brief intervention tool. It comprises screening instruments for both alcohol and other drugs, and mental health and emotional well-being. It has accompanying instructions and resources to inform a brief intervention. For more information see here.

Adapted Patient Health Questionnaire 9

The Adapted Patient Health Questionnaire 9 includes culturally- appropriate questions assessing symptoms of depression including mood, sleep, appetite, energy levels and concentration. It should be administered by a First Nations health worker; family can be included in the assessment process. For more information see here.

The Kimberley Indigenous Cognitive Assessment (KICA)

The Kimberley Indigenous Cognitive Assessment (KICA) screening tool assesses cognitive capacities associated with dementia, including orientation, naming, registration, verbal comprehension, verbal fluency, free and cued recall, praxis, and frontal executive function. For more information see here.

Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB)

The CANTAB has been found to be effective when conducting cross-cultural assessments and for individuals whom English is a second language. [11] It has also been used in studies with First Nations Australians. For more information see here.

CogState Brief Battery

The CogState Brief Battery (Identification, Detection, One Card Learning, and One Back tasks) was developed as a response to the need for appropriate cognitive assessments for First Nations Australians. It was designed so that performance on these computerised tests should not be affected by language or cultural factors. It has been found to have greatest acceptability in young-to middle-aged participants with some education. [12] For more information see here.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)

The DSM-5 provides ‘Cultural Formulation Interview’ guidelines to support assessment and treatment.

First Nations peoples with intellectual disability may experience an added layer of communication complexity. It is important to carefully consider their communication needs. Some First Nations peoples may prefer a worker who speaks their language and understands their culture, while others may prefer someone outside their community.

If appropriate, involve Aboriginal Health Workers, Aboriginal Mental Health Workers, and family members and interpreters. If the interpreter is not a family member, it can be beneficial to have the same interpreter attend each session to support the development of short-hand and rapport between the interpreter and the person.

You can find more information about adapting communication for people with intellectual disability broadly here.

Translation and interpreter services

- There are a variety of sign languages used by First Nations peoples. National Interpreting & Communication Services (NICSS) provides sign language interpreters for a range of professional and government services, including public and private hospitals. The hours can be billed under NDIS interpreting hours.

- The Translating and Interpreting Service offers interpreting services for non-English speakers. You can access immediate phone interpreting or pre-book a phone or on-site interpreter. You can call them on 131 450.

- NSW Health Care Interpreting Services provides free, confidential and professional interpreters for individuals who use public health services. Upon contact, the service directs people to the First Nations liaison officer for the hospital or Local Health District.

- 2M Language Services has qualified interpreters in First Nations languages. They do on-site, telephone and video remote interpreting for a fee.

- Lifeline offers interpreters (through the Translating and Interpreting Service) as part of their services. You can call them on 13 11 14.

You can play an important role in advocating for accessible services for First Nations peoples with intellectual disability. For example, you can:

- encourage training and education in cultural competence within your organisation or service

- be aware of hospital liaison officers who can support First Nations peoples

- be aware of interpreters who have experience working with people with intellectual disability in your local community

- use and promote the use of Easy Read and plain English resources for the people you support

- use case studies and success stories to help motivate change.

The First Peoples Disability Network Australia has more information about how to advocate for First Nations peoples with disability.

Key resources

First Nations health organisations and services

- First Peoples Disability Network Australia is a national human rights organisation of and for Australia’s First Peoples with disability, their families and communities.

- National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) has Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services and Aboriginal Medical Services in each state and territory. Services include, but are not limited to:

- psychological therapies

- complex mental health support

- case management

- clinical care co-ordination.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health program funds Primary Health Networks to engage culturally appropriate mental health services for First Nations peoples.

- Indigenous Allied Health Australia leads sector workforce development and support to improve the health and wellbeing of First Nations peoples.

- Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NSW assists Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services across NSW to ensure they have access to an adequately resourced and skilled workforce to provide high quality health care services for First Nations communities.

- Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet provides a search tool to help you find First Nations health workers and health practitioners by area.

- The National Indigenous Postvention Service offers support to First Nations peoples and their communities who have been affected by suicide. You can call them on 1800 805 801.

Social and emotional wellbeing resources and tools for First Nations peoples

- Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NSW has social and emotional wellbeing resources, including posters, toolkits and wellness cards that can be shared with First Nations peoples.

- WellMob has social, emotional and cultural wellbeing online resources for First Nations peoples in a variety of formats, including apps, websites, audio, documents, videos and social media.

- The Black Dog Institute has social and emotional wellbeing resources for First Nations people, including a Lived Experience Centre and iBobbly, a wellbeing self-help app for young First Nations peoples aged 15 years and over.

Other services to support mental health and wellbeing

- The Department of Communities and Justice has free mediation and conflict management services aimed at improving safety and harmony in Indigenous communities

- All Together Now has information on how to report racism and self-care and counselling options.

- NSW Aboriginal Safe Gambling Service manages the NSW GambleAware Aboriginal Service. They provide education and counselling services to First Nations peoples affected by gambling issues.

- Your Room offers information and services that support First Nations peoples in NSW to reduce harm caused by alcohol and drugs. It also provides culturally safe telephone counselling and referral services.

- Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice provides a comprehensive guide to inform practices of mental health professionals supporting First Nations peoples.

Services and training programs that can support improvement of your cultural competency

- AIATSIS’s Core cultural learning is an online course with 10 interactive modules.

- Centre for Cultural Competence Australia has an online cultural competency course. They also provide consulting services.

- Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association has training designed for doctors, nurses, health care workers, students, government organisations and universities.

- Mirri Mirri offers programs and professional workshops for individuals and organisations. They also offer culturally-focused services for organisations aimed at developing relationships and engagement with First Nations communities.

- BlackCard delivers cultural education workshops, training, and consultancy.

Translation and interpreter services

- There are a variety of sign languages used by First Nations peoples. National Interpreting & Communication Services (NICSS) provides sign language interpreters for a range of professional and government services, including public and private hospitals. The hours can be billed under NDIS interpreting hours.

- The Translating and Interpreting Service offers interpreting services for non-English speakers. You can access immediate phone interpreting or pre-book a phone or on-site interpreter. You can call them on 131 450.

- NSW Health Care Interpreting Services provides free, confidential and professional interpreters for individuals who use public health services. Upon contact, the service directs people to the First Nations liaison officer for the hospital or Local Health District.

- 2M Language Services has qualified interpreters in First Nations languages. They do on-site, telephone and video remote interpreting for a fee.

- Lifeline offers interpreters (through the Translating and Interpreting Service) as part of their services. You can call them on 13 11 14.

Additional background information

First Nations peoples are more likely to have been in contact or had a family member in contact with the criminal justice system than the general population. A person who has come into contact with the criminal justice system may be a victim, witness or perpetrator of a crime. Despite making up around 3% of the Australian population, First Nations peoples account for just over 25% of the total Australian prisoner population. [4] In addition, people with intellectual disability, many of whom have a mental illness, are also over-represented in Australian prisons. You can read more about people with intellectual disability who have come into contact with the criminal justice system, and the relationship between intellectual disability, mental illness and offending here.

Appropriate identification of people with intellectual disability is essential within the criminal justice system to ensure that they get appropriate support. For First Nations peoples, culturally unsafe assessment tools can add a layer of complexity to accurate diagnosis. Key stakeholders in the criminal justice system, such as police, lawyers and correctional officers, may not have the skills and training necessary to recognise intellectual disability in First Nations peoples.

First Nations peoples with intellectual disability in contact with the criminal justice system are likely to [13, 14]:

- experience mental illness

- have contact with the police at an earlier age

- have higher levels of police contact

- not receive support from a disability service.

Within correctional or juvenile justice facilities, First Nations peoples with intellectual disabilities are more likely to have [15]:

- poorer coping mechanisms

- additional experiences of racism

- difficulties handling emotions

- discomfort around people who are not of a First Nations background

- reduced access to culturally meaningful activities in custody.

First Nations peoples also have higher instances of deaths in custody. For more information, you can view the findings from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2018 Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with Disability. Canberra: ABS; 2021. Contract No.: ABS Cat. No. 4430.0.

- Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, Dua T, Saxena S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(2):419-36.

- Wen X. The definition and prevalence of intellectual disability in Australia. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 1997.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018-19. Canberra: ABS; 2019. Contract No.: ABS cat. no. 4715.0.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: 2015. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2015.

- Gubhaju L, McNamara BJ, Banks E, Joshy G, Raphael B, Williamson A, et al. The overall health and risk factor profile of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants from the 45 and up study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1-14.

- Cunningham J, Paradies YC. Socio-demographic factors and psychological distress in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian adults aged 18-64 years: analysis of national survey data. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1-15.

- Townsend C, McIntyre M, Lakhani A, Wright C, White P, Bishara J, et al. Inclusion of marginalised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with neurocognitive disability in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). Disability and the Global South. 2018;5:1531-52.

- Laverty M, McDermott DR, Calma T. Embedding cultural safety in Australia’s main health care standards. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2017;207(1):15-16.

- Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181-4; discussion 200-1.

- Sahakian BJ and Owen AM. Computerized assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB: discussion paper. J R Soc Med. 1992;85(7): 399-402.

- Thompson F, Cysique LA, Harriss LR, Taylor S, Savage G, Maruff P, et al. Acceptability and Usability of Computerized Cognitive Assessment Among Australian Indigenous Residents of the Torres Strait Islands. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2020;35(8): 1288-302.

- Heffernan E, Andersen K, McEntyre E, Kinner S. Mental disorder and cognitive disability in the criminal justice system. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd Edition Canberra, ACT, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia. 2014:165-78.

- Bawdrey E, Dowse L, Clarence M. People with intellectual and other cognitive disability in the criminal justice system: University of New South Wales; 2012.

- Shepherd SM. Aboriginal prisoners with cognitive impairment: Is this the highest risk group? Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. 2017(536):1-14.