Treatment

Jump to a section below

Key points

- The person with intellectual disability should be central to decisions about their treatment.

- Become aware of issues around prescribing psychotropics for people with intellectual disability.

- Modified versions of psychological therapies including cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness have been found to be effective when working with people with intellectual disability.

- Involve support networks where possible to support and monitor treatment approaches.

- Ensure that regular follow-ups are scheduled; people with intellectual disability may not seek assistance if they are experiencing side effects or if a treatment is not working for them.

This section provides key information around treatment planning and providing pharmacological and psychological interventions for people with intellectual disability. Considerations for specific service types are provided at the end. You may also like to view 3DN's Intellectual Disability Health Education course Management of Mental Disorders in Intellectual Disability for a small fee or which is available free of charge for NSW Health professionals through My Health Learning on HETI. There is also additional information in the Treatment section (page 31) of the Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit.

Below are key considerations and key questions you may have when working with people with intellectual disability during the treatment stage.

For a list of specialist health services for people with intellectual disability see Specialist intellectual disability services.

Key considerations

Treatment, or care planning should be underpinned by the guiding principles of managing mental ill health in people with intellectual disability, including recovery-oriented practice. See further information in the Guiding principles section. Consider the following when planning the most appropriate treatment approach.

- Ascertain and consider the wishes of the person with intellectual disability and their thoughts on treatment options; they should be viewed as experts in their own life. Also take into account the views and expertise of support networks.

- Review evidence-based guidelines where available, for example:

- Developmental Disability guidelines from Therapeutic Guidelines (a subscription website), including managing psychiatric disorders in people with developmental disability.

- Prescribing guidelines for people with intellectual disability, Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit, page 34.

- The Centre for Developmental Disability Health’s Healthcare for adults with intellectual disability Clinical Guideline and/or autism spectrum disorders: Clinical Guideline. Monash Health which includes information also relevant to mental health.

- NICE Guidelines from the UK

- Mental health problems in people with learning disabilities: prevention, assessment and management

- Care and support of people growing older with learning disabilities

- Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges

- Speak to the person with intellectual disability directly, explaining any procedures or treatment in a way they can best understand (e.g. by drawing diagrams). Provide them with information that they can take away with them.

- The supports required and the need for a multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary team. Where possible, integrate information into a single care plan. If multiple care plans are unavoidable, check that they are not conflicting.

- How the person’s needs will be met and practical considerations such as how they will get to their appointments.

- Care, or treatment, plans include:

- strategies for triggers that can affect mood

- signs that mental health is deteriorating

- early intervention and crisis prevention

- crisis management

- who the person or their support networks can contact in different situations

- plans for monitoring and follow-up.

Carers, family members, and support workers (particularly in a group home environment) should have a copy of the care plan so that they are aware of health appointments, consistent approaches are used, and they know what to do in a crisis.

After a review of the person’s functioning, it may be decided that the individual requires an NDIS behaviour support plan.

A behaviour support plan is developed with the person with intellectual disability, their carers, family, health professionals, and other supporters to put in place evidence-based strategies to improve their quality of life. For example, it may include de-escalation strategies in acute situations. See the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission for information on behaviour support for participants and providers.

An NDIS behaviour support plan must be developed by a behaviour support practitioner who is registered with the NDIS to provide specialist behaviour support. They must meet standards outlined in the Positive Behaviour Support Capability Framework. Encourage carers and family to speak to their NDIS Support Coordinator or contact local disability support providers to find a suitable behaviour support practitioner in their area.

3DN's Intellectual Disability Health Education course Challenging behaviour is available for a small fee or free of charge for NSW Health professionals through My Health Learning on HETI.

Before starting any treatment, informed consent must be obtained from the person, or their guardian or person responsible. It is not always obvious whether a person has capacity to consent, and if they do, whether they are consenting to treatment.

- Become familiar with the laws in your state or territory that guide decision-making and consent for people with disability. For information on capacity to consent and supported decision-making in NSW, see the NSW Trustee & Guardian website which includes a Capacity Toolkit. There is also information in 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit (page 29) and Intellectual Disability Health Education course Consent, Decision-Making and Privacy – A Guide for Clinicians.

- Determine if the person usually makes treatment/other health decisions themselves. Assess capacity separately for each decision; they may be able to provide their own consent for some decisions, but not others. Regardless of their capacity to provide consent, best practice is to still involve the person.

There is a tendency for psychotropic medications to be inappropriately prescribed for people with intellectual disability, including excessive dose or prolonged treatment without review, overuse to manage behaviours of concern, polypharmacy, and no regular monitoring of side effects. [1, 2] The following are initial considerations when prescribing psychotropic medications for people with intellectual disability.

Indications

- Psychotropic medication may be indicated for:

- severe mental disorders or milder cases of depression and anxiety that have not responded to psychological treatments alone, or complex cases [3]

- behaviours of concern that are severe and non-responsive to behavioural or cognitive therapy, and are significantly affecting the person’s or family/support persons’ life. [4]

- Chemical restraint using psychotropics is a form of restrictive practice that is used when a person with intellectual disability presents with behaviours of concern. Medication can become over-relied on without addressing the underlying causes, [5] leading to long-term negative side effects. [6] It is advisable that medication is not used as a first step approach without trialling behavioural or environmental interventions first. See the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission Regulated Restrictive Practices Guide for more information. Read more about the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation of People with Disability’s public hearing on Psychotropic medication, behaviour support and behaviours of concern.

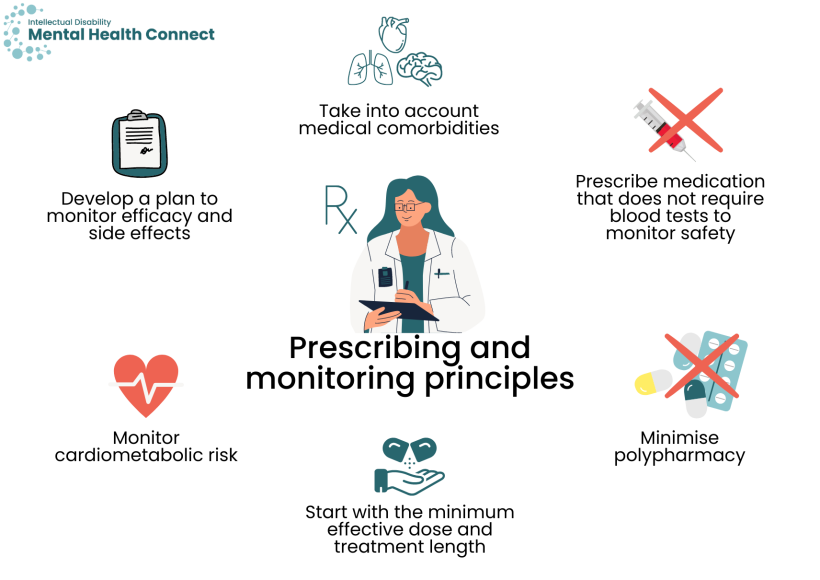

Prescribing and monitoring principles

If pharmacological treatment is indicated, follow best practice principles of prescribing and monitoring for people with intellectual disability including:

- taking into account medical comorbidities. For example, if a person with intellectual disability has epilepsy, choose a medication with minimal effect on seizure threshold

- minimising polypharmacy and considering potential interactions with existing medication. See the STOMP (Stopping over medication of people with a learning disability, autism, or both) resources from the United Kingdom. They have a medication pathway with information to help ensure people with intellectual disability only take the medication they need safely. There is also an Australian network, STOMPOZ. The NDIS Commission also have a Practice Alert on polypharmacy.

- prescribing medication that does not require blood tests to monitor safety if the person refuses blood tests

- minimising polypharmacy and considering potential interactions with existing medication

- starting with the minimum effective dose and treatment length, which may be less than the general population (people with intellectual disability can experience more side effects). Medications are best ‘trialled’ rather than ‘commenced’.

- monitoring cardiometabolic risk. Resources are available on 3DN’s Positive Cardiometabolic Health for People with Intellectual Disability webpage and 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education has a course on Cardiometabolic Health in People with Intellectual Disability available for a small fee.

- developing a plan to monitor efficacy and side effects. See the Monitoring treatment response section below for more information.

For more detailed guidelines when prescribing psychotropic medications to people with intellectual disability see page 34 of 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit. There is also a series of podcasts on Responsible Psychotropic Prescribing to People with an Intellectual Disability that outline considerations for adults and children and adolescents.

Types of therapies

Psychological therapies form the basis of treatment for people with intellectual disability with mild depression and mild anxiety. Also consider them as an adjunct to psychotropic treatment. Evidence suggests that psychological interventions are effective in treating many conditions for people with intellectual disability. [7] Consider the following with regard to psychological therapies.

- Environmental and behavioural interventions can also be trialled as a first-line treatment before considering medication.

- Implementing changes in a person’s lifestyle and social situations can be part of their care plan. This may include:

- changes to day-to-day support (changes in level of disability support, increased respite etc)

- changes to weekly routine (changes in hours at work/day program, outings that are less stressful for the person)

- exercise regime and healthier diet

- involvement in community activities, social programs, hobbies, or further education in areas that are of interest to the person.

- There is growing research and evidence for the use of psychological therapies for people with intellectual disability including:

- cognitive behavioural therapy, [8] including visual cognitive behaviour interventions, [9] computerised CBT for anxiety, [10] and interventions using gaming and mobile technology such as Pesky gNATs

- dialectical behaviour therapy [11, 12]

- family systems therapy, including during life transitions [3, 13]

- counselling. [3]

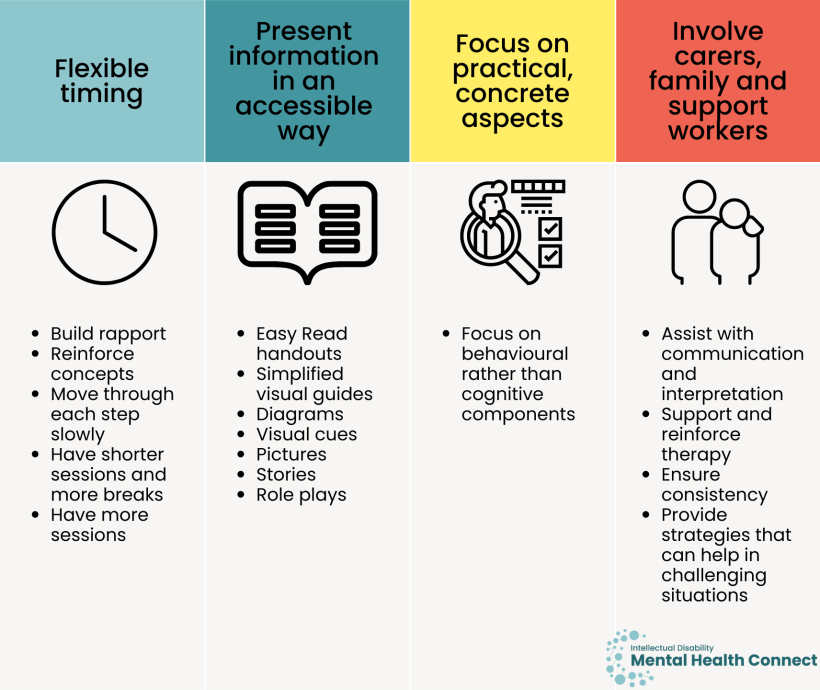

Modifications and practical considerations

Considerations need to be made as to how the needs of people with intellectual disability can be met when undertaking psychological treatments. These include the following.

- Flexible timing, for example spending more time:

- building rapport (people with intellectual disability and their supporters tell us how important rapport and trust are)

- reinforcing concepts

- moving through each step more slowly

- having shorter sessions and more breaks, and

- having more sessions.

- Presenting information in a way that is accessible to the person with intellectual disability e.g. Easy Read handouts, using simplified visual guides, diagrams, visual cues, pictures, stories, and role plays to convey concepts.

- If the individual has had a neuropsychological assessment, utilise results to determine the best ways to support the individual during therapy considering their cognitive strengths and weaknesses.

- Focusing on practical, concrete aspects of therapy rather than abstract concepts, and behavioural rather than cognitive components.

- Involving carers, family, and support workers to:

- assist with communication and interpretation during appointments

- support and reinforce therapy strategies (e.g. encouraging self-soothing and practising techniques at home)

- ensure everyone is using consistent strategies and language/terms for these strategies and tools

- equip them with strategies that can help in challenging situations.

Regular monitoring and review of treatment often does not occur for people with intellectual disability. It is vital to plan how treatment response will be monitored and follow up regularly, preferably involving support networks where possible.

- Planned, systematic monitoring is important for people with intellectual disability as they are:

- less able to advocate for themselves and assertively ask for their needs to be met

- less likely to recognise that a symptom is a side effect that could be managed with a medication review

- less able to identify whether a psychotropic or psychological therapy is effective.

- People can fill out a mood diary or feelings chart (such as the My Feelings Chart on page 48 of the Feeling Down: Looking After My Mental Health Easy Read guide).

- Ask the person with intellectual disability directly how they are finding medications and if they are experiencing side effects in an accessible way. People with intellectual disability report that they are often not asked this (like the general population would be).

- Discuss with carers, family members and support workers whether they can assist with monitoring at home. This could involve completing side effect or mood diaries that can be shared at follow-up appointments. For example, they could complete a record such as Black Dog’s Daily Mood Chart on behalf of the person they support.

Key questions

People with intellectual disability can have complex biopsychosocial needs and may not respond to treatments in the same way as the general population. As such, the treatment response may not be as desired, and more than one treatment may need to be trialled.

- Consider whether there may be another cause of mental ill health or behaviours of concern such as environmental reasons (e.g. where the person is living) or physical health (an undetected medical condition that needs to be investigated).

- Undertake a medication review.

- Referral to a higher tier of care may be required e.g. if the person with intellectual disability is being treated through a primary care provider, consider whether referral to a psychiatrist is required.

- If support networks are not involved in care, explore whether there are any family members or friends who could support the person to engage with their care plan and help with monitoring. If not, consider the most appropriate support in consultation with the person with intellectual disability and take active steps to arrange this (e.g. paid support worker through their NDIS plan, community mental health service outreach teams, community nurse, or case worker).

For further advice around clinical impasses see the Clinical stalemates section.

Seeking specialist assistance

You can seek assistance from a colleague or other professionals who specialise in this area, or from specialist intellectual disability mental health services such as the Statewide Intellectual Disability Mental Health Outreach Service. See more information on specialist intellectual disability mental health services.

- Consider consultation with a specialist intellectual disability mental health service if:

- symptoms do not improve or worsen despite treatment

- the presentation is more complex than originally thought during assessment

- there is a deteriorating or unexpected course

- there is a continuing high risk to the person despite treatment (e.g. self-harm or expressed suicidal ideation).

- During the treatment phase, support can include:

- short-term management until adequate mainstream services are available

- providing specialist advice around psychotropic and psychological therapies

- case review when treatment is not working as planned.

- While waiting for case review from specialist services or access to private specialists with long waiting lists, professionals can:

- seek out interim advice from intellectual disability health and mental health teams or staff in consultation roles such as Clinical Nurse Consultants

- see if the psychiatrist you have referred the person to may be able to offer prescribing advice over the phone or email until they can be seen

- undertake capacity building activities or mentoring to learn more about a particular issue

- support the person to access any disability or community supports that may help to support their mental health.

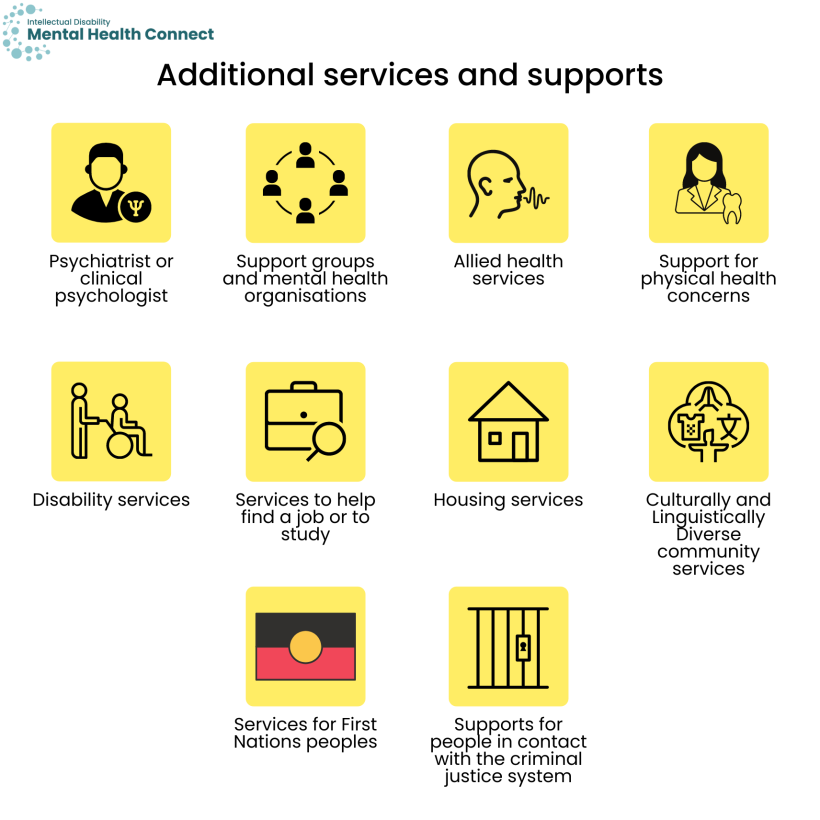

Depending on the current mental health provider/multidisciplinary team, at all stages of the treatment phase, consider whether the person with intellectual disability would benefit from other services. These may include:

- referral to a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist

- support groups and mental health organisations

- allied health services e.g. occupational therapist, speech pathologist

- support for physical health concerns including dentistry

- disability services e.g. behaviour support, supporting daily life skills, respite, community activities, day centres

- services to help find a job or to study

- housing services

- Culturally and Linguistically Diverse community services

- Services for First Nations peoples

- supports for people in contact with the justice system.

See Services for mental health (within the people with intellectual disability section) for more information.

Caring and providing support to a person with intellectual disability and mental ill health or behaviours of concern can be distressing, stressful and time-consuming for support networks.

- Check whether carers, family members and support workers require support themselves. This could include being connected with carers’ organisations such as Carers NSW and support groups, or psychological support/counselling themselves. Encourage them to see their GP if they have mental health concerns of their own.

- Equip support networks to implement the care plan. Understand and work to overcome barriers that they may face to implement the plan.

- More regular respite care may be required. Have a discussion with carers and family members about options in their area.

- You can encourage them to view the Looking after myself section for more information.

- Carers Australia have a fact sheet on How social prescribing could improve health and wellbeing of carers that can help carers to access community supports and activities to help reduce their isolation and improve their wellbeing.

People with intellectual disability are more likely to present to emergency departments and have psychiatric re-admissions after a previous psychiatric admission than those without intellectual disability. [14]

Predictors of emergency department admission for people with intellectual disability include:

- not having a GP/family doctor

- not having a crisis plan

- living with family (as opposed to a group home)

- prior visits to the emergency department, indicating that issues are either not resolved during an initial visit, or visiting the emergency department is the best option at the time. [15]

Carers report that one of the main reasons they take the person with intellectual disability they support to the emergency department is because of behaviours of concern and a lack of community resources. [16]

The following considerations and actions can help prevent people with intellectual disability requiring acute care or admissions.

- It is important for people with intellectual disability to have regular appointments with their GP or be assisted to find a GP who they can see on a long-term basis if they do not have one.

- At the primary care level, proactively identify mental health issues early and establish a management plan to avoid the need for acute care services. Refer to specialists and allied health professionals with experience in intellectual disability mental health, and intellectual disability mental health specialists when required.

- Create a crisis plan so the person and their support networks know what to do if their mental health worsens or if behaviours of concern become more difficult to manage, including who to contact and helplines they can utilise out of hours. This can help prevent the need to use emergency departments.

- If a person is admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit, a comprehensive discharge plan has an important role in ensuring the person has appropriate ongoing support to prevent future emergency department presentations and admissions. See the Transfers of care section for more information about discharge planning.

- Connect people with intellectual disability and complex needs to community mental health Assertive Outreach Teams. These teams provide regular, ongoing contact to people with severe or long-term mental illness. They can assist with service co-ordination, advocacy, and rehabilitation. You can search for teams using the WayAhead Directory.

Considerations for specific services

- Discuss developing a Mental Health Treatment Plan through the Better Access initiative with the person with intellectual disability and their supporters.

- Ensure access to information suitable for each audience including Easy Read.

- If a multidisciplinary team is involved in the person’s care plan, co-ordinate care and maintain regular follow-up. See the Working with people with intellectual disability and their team section for more details.

- Schedule regular follow-up appointments to monitor how the person is progressing. Ask how they are finding their psychiatrist or allied health professionals. Let them know it is OK to change health workers if they want.

- Also see the Intake and Assessment and diagnosis sections for more information around providing care for people with intellectual disability within primary care.

- Even if there is limited time, still speak to the person with intellectual disability directly, explaining any procedures or treatment in a way they can best understand (e.g. by drawing diagrams, ensuring commonly provided information is available in Easy Read format).

- Outline potential options at this point to the person with intellectual disability and their support networks e.g.

- admission to Psychiatric Emergency Care Centre (PECC)/inpatient ward

- organise outpatient appointment with a psychiatrist

- return to GP.

Talk through what each option will mean for them. Ask for input from the person and their supporters and decide on a plan together. Explain the next steps to the person in an accessible way.

- Also see the Intake, Assessment and diagnosis, and Transfers of care sections for more information around providing care for people with intellectual disability in emergency departments.

- As inpatient stays can be challenging for people with intellectual disability, discuss how the person’s supporters could be involved during their stay e.g. providing support through the day.

- Provide Easy Read information; 3DN has Easy Read Introduction to inpatient mental health services templates that inpatient services can tailor to meet their individual needs.

- To decrease distress associated with the unknown, support procedures and routines with structured visuals to create predictability.

- It is helpful if hospital staff know the person’s needs and likes so that they can best support them e.g. ‘Top 10 things to know about me’ lists/‘Top 5 interventions’ if the person is distressed.

- People with intellectual disability and their support networks speak of the importance of someone to talk to in hospital. Ensure the person has access to e.g. a social worker, psychologist, or counsellor.

- Seek assistance from behaviour support specialists to help people cope with e.g. their fear of needles.

- Identify strategies to help reduce the risk of long admissions, for example:

- identifying whether the person needs additional supports in the community through their NDIS plan

- assisting the person to find suitable housing if they are homeless or at risk of homelessness – see Support with your everyday life within the people with intellectual disability section for more information.

- developing a behaviour support plan if behaviours of concern are preventing discharge

- seeking assistance from e.g. a social worker to assist if there are any administrative barriers preventing appropriate supports in the community.

- Also see the Intake and Assessment and diagnosis sections for more information around providing care for people with intellectual disability within inpatient settings.

Resources

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education course Management of Mental Disorders in Intellectual Disability

- Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit- Treatment section (page 31)

- Responsible Psychotropic Prescribing to People with an Intellectual Disability podcasts that outline considerations for adults and children and adolescents.

- NHS STOMP ‘Stopping over medication of people with a learning disability, autism or both’ resources. There is also an Australian network, STOMPOZ.

- NDIS Commission Practice Alert on polypharmacy.

- Clinical guidelines

- Developmental Disability guidelines from Therapeutic Guidelines (a subscription website), including managing psychiatric disorders in people with developmental disability.

- Prescribing guidelines for people with intellectual disability, Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit, page 34.

- The Centre for Developmental Disability Health’s Healthcare for adults with intellectual disability Clinical Guideline and/or autism spectrum disorders: Clinical Guideline, Monash Health which includes information also relevant to mental health.

- NICE Guidelines from the UK

- Mental health problems in people with learning disabilities: prevention, assessment, and management

- Care and support of people growing older with learning disabilities

- Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges

- For information on behaviours of concern and behaviour support plans

- NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission information on behaviour support for participants and providers

- NDIS Commission Positive Behaviour Support Capability Framework

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education course Challenging behaviour

- For information on chemical restraint

- NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission Regulated Restrictive Practices Guide

- Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation of People with Disability’s public hearing on Psychotropic medication, behaviour support and behaviours of concern.

- For information on supported decision-making and capacity to consent

- 3DN has resources on supporting Positive Cardiometabolic Health for People with Intellectual Disability.

- McGillivray JA and McCabe MP. Pharmacological management of challenging behavior of individuals with intellectual disability. Research in developmental disabilities. 2004;25(6): 523-537.

- Deb S, Kwok H, Bertelli M, Salvador-Carulla L, Bradley E, Torr J, et al. International guide to prescribing psychotropic medication for the management of problem behaviours in adults with intellectual disabilities. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(3): 181-186.

- Therapeutic Guidelines Limited, Management guidelines: developmental disability. Version 3. 2012, Therapeutic Guidelines Limited: Melbourne.

- Trollor JN, Salomon C, and Franklin C. Prescribing psychotropic drugs to adults with an intellectual disability. Australian Prescriber. 2016;39(4): 126-30.

- Bowring DL, Totsika V, Hastings RP, Toogood S, and McMahon M. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use and association with challenging behaviour in adults with an intellectual disability. A total population study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2017;61(6): 604-617.

- Deutsch SI and Burket JA. Psychotropic medication use for adults and older adults with intellectual disability; selective review, recommendations and future directions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104: 110017.

- Andrews G, Dean K, Genderson M, Hunt C, Mitchell P, Sachdev P, et al., Management of Mental Disorders: 5th Edition. 2013, United States: CreateSpace.

- Hronis A. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for People with Intellectual Disabilities – How Far Have We Come? International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2020. 14(6): p. 1-19.

- Carney M, Visual Cognitive Behavioural Intervention: An Adaptation of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for People with Intellectual Disability and Mental Health Difficulties, in School of Education. 2018, Flinders University.

- Cooney P, Jackman C, Coyle D, and O'Reilly G. Computerised cognitive–behavioural therapy for adults with intellectual disability: randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;211(2): 95-102.

- Lew M, Matta C, Tripp-Tebo C, Watts D, and Ed M. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for individuals with intellectual disabilities: A program description. Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities. 2006. 9(1): p. 1-12.

- Jones J, Blinkhorn A, McQueen M, Hewett L, Mills-Rogers M-J, Hall L, et al. The adaptation and feasibility of dialectical behaviour therapy for adults with intellectual developmental disabilities and transdiagnoses: A pilot community-based randomized controlled trial. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(3): 805-817.

- Taylor WD, Cobigo V, and Ouellette-Kuntz H. A family systems perspective on supporting self-determination in young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(5): 1116-1128.

- Li X, Srasuebkul P, Reppermund S, and Trollor JN. Emergency department presentation and readmission after index psychiatric admission: a data linkage study. BMJ open. 2018;8(2): e018613.

- Lunsky Y, Balogh R, and Cairney J. Predictors of emergency department visits by persons with intellectual disability experiencing a psychiatric crisis. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.). 2012;63(3): 287-90.

- Weiss JA, Lunsky Y, Gracey C, Canrinus M, and Morris S. Emergency Psychiatric Services for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities: Caregivers’ Perspectives. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2009;22(4): 354-362.