Communication

Jump to a section below

Key points

- People with intellectual disability can experience communication difficulties, especially those with severe and profound levels of intellectual disability.

- Communication difficulties can act as a barrier to seeking and receiving adequate health care.

- Effective communication can mitigate these barriers and help professionals uphold the rights of people with intellectual disability through provision of accessible services and care.

- It is key to speak directly to the person with intellectual disability, not just their support person. Find out what the person's preferred communication strategy is and encourage them to use it e.g., use of a communication device.

- This section provides practical tips, information on communication tools and how professionals can make information accessible to support effective communication.

Importance of good communication

Effective communication is fundamental to the provision of quality mental health care and wellbeing supports for all individuals, including people with intellectual disability. People with intellectual disability can experience communication difficulties, especially those with severe and profound levels of intellectual disability. They may have problems with their speech sounds or understanding and using language. While people with mild intellectual disability will likely have the necessary expressive and receptive language skills to verbally take part in assessments and appointments, those with moderate to profound levels of intellectual disability may use methods other than speech.

Communication is the process of receiving and expressing messages verbally (e.g. language and speech sounds) and non-verbally (e.g. gestures and communication tools). Behaviour is a form of non-verbal communication and can be a valuable source of expressive information. All behaviour has a function. For example, an individual's behaviour could be communicating:

- psychological symptoms

- emotions, health problems

- pain, hunger, or

- something about a situation that is currently occurring.

As a person’s level of intellectual disability becomes more severe, atypical presentations of symptoms become increasingly common, and professionals are more likely to encounter ‘behavioural equivalents’ of psychiatric symptoms. Behavioural equivalents are the expression of signs and symptoms of mental illness through behaviour rather than through verbal description.

The impact different mental illnesses, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizophrenia, have on communication can be exacerbated in people with intellectual disability (e.g. slow speech associated with depression may also present in people with intellectual disability as reduced verbalisation).

For people with intellectual disability, communication difficulties can be a barrier to seeking and receiving adequate health care. Without effective communication, people may not:

- receive important information about their health,

- nor express and make choices about their health and wellbeing.

Effective communication can mitigate these barriers and help you uphold the rights of people with intellectual disability through the provision of accessible services and care. It is important to remember that difficulty with communication does not mean that someone cannot understand and make decisions.

To find out more about the importance of good communication with people with intellectual disability see Mencap’s Communication: speaking to people with a learning disability video.

Disability professionals

Disability professionals often play an important role in supporting the development of communication skills in people with intellectual disability and their support networks. Disability professionals can also support mental health professionals to determine and adapt to the preferred communication methods of the person with intellectual disability.

Want to learn more?

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education provides online, self-paced training in intellectual disability mental health. There is a specific communication course for health professionals with more information on how you can improve your communication with people with intellectual disability. These courses can be accessed for a small fee. A selection of courses is also available for free through My Health Learning on HETI for NSW Health staff members.

- The Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework: A Manual for Mental Health Professionals describes the specific skills and attributes required by mental health professionals for the provision of quality services to people with intellectual disability. It is accompanied by The Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework: A Practical Toolkit for Mental Health Professionals. The Toolkit provides practical information, assessment tools and links to resources to assist in the development of the core attributes, including communication, described in the Framework Manual.

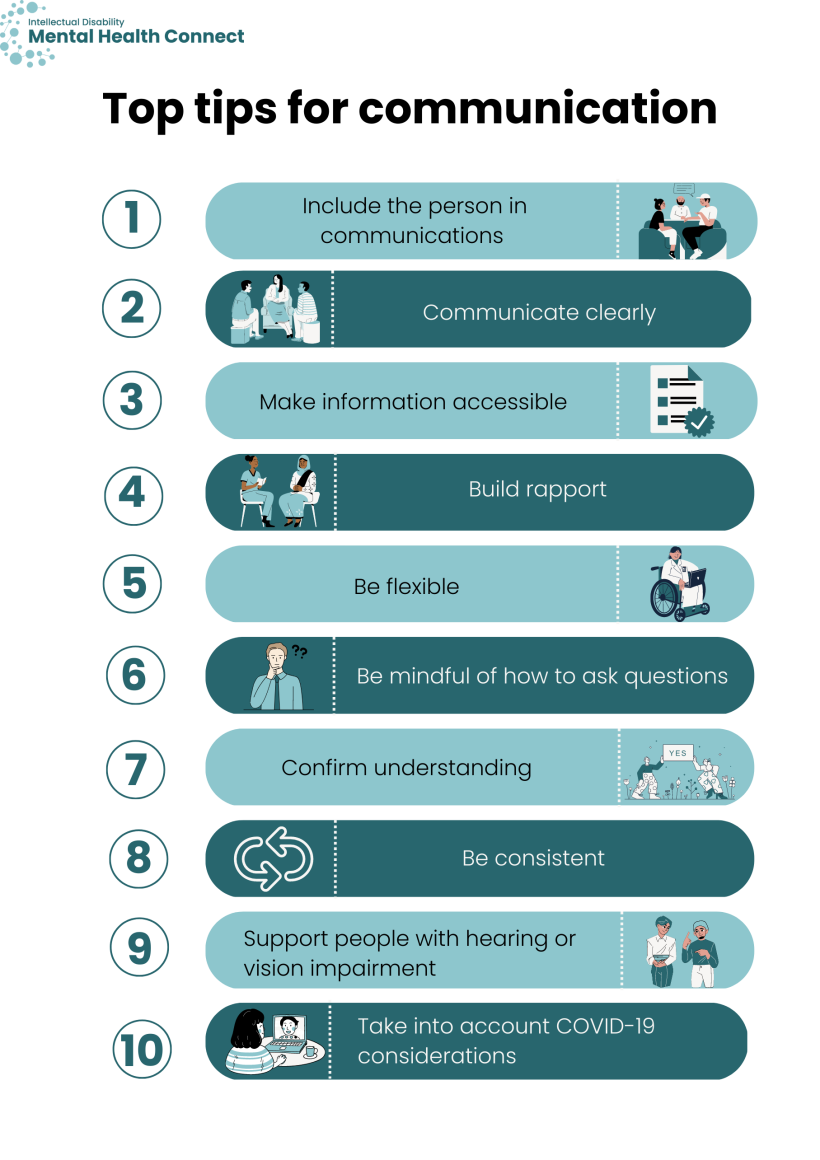

Top tips for communication with people who find speech or language difficult

Everybody is different; it is important to discuss with the person or their support network what communication strategies you could adopt for their appointment. Below are different ways to modify your communication to work effectively with people who find speech or language difficult. However, the professional should try to use the person’s preferred strategies before introducing anything new.

To find out more about how you can communicate more effectively with people with intellectual disability see Change’s How can I communicate better with people with learning disabilities video.

Professionals can support inclusion of the person in their health care by speaking directly to them (not just to their supporters) and using their preferred language. You can ask the person and their support network whether they prefer person-first language or identity-first language.

- Person-first language places the individual first rather than their disability or impairment. It describes what they have, rather than who they are, i.e. a person with intellectual disability. The person-first language reminds people that we are talking about individuals and contributes positively to community attitudes about people with a disability.

- Some people may prefer identity-first language, for example, ‘autistic person’ rather than ‘person with autism’.

Professionals can also support inclusion by using the preferred communication methods of the person with intellectual disability and, if required, request assistance from a support person or carer to interpret the person’s communication methods. People communicate in different ways. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is any communication strategy used by people with communication difficulties. AAC methods can be an alternative or addition to speech. Communication tools and accessible information are examples of ACC. AAC can be unaided or aided.

Unaided AAC

- Body movements

- Facial expressions

- Pointing and finger spelling

- Sign language

- Natural gesture or natural sign language

- Key Work Sign combines signing and natural gestures

- Idiosyncratic signals (someone’s personal signs or behaviours)

Aided AAC

- Written text

- Pictures and symbols

- Communication boards, cards, or books

- Real objects (e.g. a water glass to take medication)

- Electronic talking devices

- Visual representations of words/concepts e.g. Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)

Speaking directly to the individual with intellectual disability is central to person-centred care. It also facilitates improved information gathering and helps to build rapport.

You can find out more about communication tools and making information accessible below.

To find out more about adapting your communication to the individual, see Autism Association of Western Australia’s video on Total communication.

You can support the person with intellectual disability’s understanding by speaking clearly and using short sentences. You can communicate clearly by:

- breaking down ideas into key points and presenting each point separately (or using a separate sentence for each point for written text)

- speaking at an average speed

- being specific and avoiding jargon, technical words or concepts

- supporting language with gestures and facial expressions

- using an interpreter to support your appointments, if required and with permission of the person or their guardian

- using an age-appropriate tone

- rephrasing what you are trying to say if the person does not understand you

- talking at an appropriate volume.

Accessible information is important to assist people with intellectual disability to participate in and make decisions about their mental health care and wellbeing supports.

Easy Read and plain English information can help your expressive language and facilitate the person’s understanding of services and care. For more information on making information accessible, see 3DN’s Making mental health information accessible for people with intellectual disability – A Toolkit.

Building rapport is important. People with intellectual disability report that they find it easier to talk to professionals if they feel comfortable and trust them. [1]

You can build rapport by:

- engaging the person before asking more formal questions

- having a positive and patient attitude towards working with the person

- speaking directly to the person

- speaking and asking about something that is of interest to the person.

People have a diverse range of communication abilities and strategies so it is important to be flexible and make adaptations to your approach. Some strategies you could use include:

- allowing extra time for the person to process and respond

- minimising distractions in the environment

- using a whiteboard or drawings and Easy Read to explain complex concepts (see Making information accessible below).

- using a graphic organiser such as a visual schedule of what will be covered in the appointment and other visual aids; this can create structure and predictability in your sessions

- using first–then language; first, can we talk about X and then return to Y. This helps discussions to remain on topic.

- explaining concepts in a way that is relevant to the individual (e.g. using specific events or activities the person enjoys or dislikes to begin discussions about feelings).

The way you ask questions is important to support the person’s comprehension.

Ask one question at a time and try to use open-ended questions. Some people with intellectual disability will say ‘yes’ to closed questions, even if it does not reflect how they feel or what has happened. This may be because the person wants to provide the ‘correct’ answer, please you, or does not understand the question.

Open-ended questions are generally preferable. However, they can be difficult for some people with intellectual disability to understand. If this is the case, you could offer several alternative options.

You can check in with the person with intellectual disability (and, if necessary, their support networks) to confirm that:

- your interpretation of their communication is accurate

- the person has understood what you were trying to convey.

There are several methods to confirm understanding. Some strategies you could use include:

- clarification (e.g. could you tell me in your own words?)

- the naïve questioner (e.g. I do not know much about X, could you tell me about it).

People with weaker receptive communication sometimes rely on routines and environmental cues to know what to expect or understand what is being said. Consistency in your communication can support individuals in what may be a novel situation. You can prepare by finding out about the person’s communicative strengths and common terms and phrases they use. For some individuals, finding out about cultural norms can help to facilitate good communication.

When supporting people with intellectual disability who have a vision impairment it is important to:

- verbalise more and inform the individual when entering and leaving the room as they cannot rely on the same non-verbal cues as people without vision impairment

- ensure there is good lighting.

When supporting people with intellectual disability who have a hearing impairment it is important to:

- ensure good lighting on your face

- face the person directly

- ensure your mouth is visible

- avoid exaggerating mouth movements, as this can make lip-reading more difficult

- capture their attention before communicating. You can discuss with the person how they would prefer you gained their attention (e.g. saying their name or gaining their attention visually).

Some people may use sign language such as Auslan. If appropriate, involve family members and interpreters. If the interpreter is not a family member, it can be beneficial to have the same interpreter attend each session to support the development of short-hand and rapport between the interpreter and the person. Short-hand is a method of interpreting quickly by substituting different expressions without losing the message.

It is a NSW Health policy that professional interpreters, rather than family members, are used for health consultations. However, for other services, some people may request that a family member acts as their interpreter. If this is the case, you may still want to recommend to the person the use of a professional interpreter, as family members may be reluctant to pass on negative messages or may have a lack of understanding of medical terminology that could lead to inaccuracies in the interpretation.

COVID-19 has brought about many changes to care and service provision.

In some health settings, in-person care requires facemasks for professionals and, where appropriate, people with intellectual disability. Facemasks can prove especially difficult for people who have a hearing impairment, due to an inability to lip-read and the distortion of speech sounds and muffling created by the physical sound barrier. For professionals, it may be helpful to use an accessible mask with a transparent front to support lip-reading during appointments, make a conscious effort to articulate, and allow for longer appointments.

Teleconferences present potential communication barriers for both professionals and people with intellectual disability. For example, non-verbal cues are more difficult to observe virtually. While practice and support (e.g. correct camera positioning) can help people become familiar with teleconferencing, there are additional cognitive demands that can be challenging and tiring for the person. There is also a risk that the person with intellectual disability will not be ‘seen’ or will be excluded during phone calls. Families and support networks may play a more active role in teleconferences, but it is still essential to include the person with intellectual disability.

The following actions can help support people during teleconferences:

- turn on your video. This allows people to read your lips and see your facial expressions and gestures while you speak.

- use mute when you are not talking. This reduces background noise that may be distracting and supports the person to focus on the speaker.

- use the ‘raise hand’ function or type a comment in the chat if you would like to notify the facilitator that you would like to speak.

- perform a roll call at the beginning of meetings with multiple members. This ensures people with a vision impairment are included from the start.

- introduce yourself when you start speaking or have a question in meetings with multiple members. This ensures people with a vision impairment are aware of the speaker.

- use interpreters and captioning, where appropriate.

- send an agenda or supporting documents before the meeting.

You can find out more about how you can make this information accessible below.

For more information and resources to support making teleconferencing more accessible see the Disability Advocacy Resource Unit micro course on accessible online meetings.

Communication Tools

Communication tools for sharing mental health information

Feelings thermometer

A feelings thermometer can help the person recognise how they feel. Each colour on the thermometer represents a different feeling. You can support the individual to recognise their feelings by commenting when they exhibit red, orange, yellow, green, or blue feelings. Some thermometers can also provide ideas to help the person manage their feelings e.g. what they can do to calm down if angry.

The Council of Intellectual disability has an example of a feelings thermometer on page 30 of their My Health Matters Folder.

Feelings diary

A feelings diary is also a communication tool used to share information. The person can write about or draw their thoughts and feelings in their feelings diary. You can support the individual to recognise and share their feelings using their diary. Their diary might be on paper, their phone or their computer. In their feelings diary they can write about or draw:

- something that happened

- how it made them feel

- how strong was the feeling

- how their body felt

- what they said at the time

- if they would have done anything differently at the time.

The person may not want to share their feelings diary; that is OK.

Talking Mats

Talking Mats can provide a visual framework to support people to communicate their opinions, reflect and make choices from options. They can be used to support discussions about a person’s care.

Other communication tools

Key Word Sign

Key Word Sign Australia was formerly known as Makaton Australia. Key Word Sign is the use of manual signs and natural gestures to support communication. Key Word Sign Australia supports children and adults with communication and language difficulties and provides resources to families, support persons and professionals.

Speakbook

Speakbook is a communication tool for people who cannot speak or use their hands. With Speakbook, individuals can communicate using only their eyes.

The Hospital Communication Book

This Hospital Communication Book contains valuable information about why people may have difficulties understanding or communicating, tips to help improve communication, and pages of pictures you can use to assist communication.

Picture Communication Tool

The Picture Communication Tool comprises sets of drawings that can be used with people who use less verbal communication. The illustrations are free to download and are ready for printing.

Communication passport

A communication passport outlines the person’s preferred communication style so that others can be better communication partners. It is founded on a person-centred, strengths-based approach. The passport combines information from several people, and from multiple contexts in the past and the present. A communication passport can be helpful for health workers who have recently started working with the person with intellectual disability, helping them obtain key information. Below are some examples of communication passport templates:

- My Communication passport

- The Council for Intellectual Disability’s My Health Matters folder has a section for outlining a person’s communication style.

Communication Guides

Your guide to Communicating with people with profound and multiple learning disabilities – Produced by Mencap in the United Kingdom, these guides are designed to provide an introduction to communication and the problems faced by someone with an intellectual disability. The guides also contain tips on how to be a better communicator and assist someone with an intellectual disability to get their message across.

Social stories and comic strip conversations – Produced by the National Autistic Society in the United Kingdom, these guides are designed to provide an introduction to social stories and comic strip conversations. Social stories and comic strip conversations can help people with intellectual disability develop a greater social understanding of emotions. They are short descriptions of a particular situation, event or activity, with specific information about what to expect in that situation and why. It can be helpful to personalise these stories to the individual. For example, a social story of their favourite place to visit and recognition of the range of emotions they usually express, from excitement (getting ready), happiness (arriving) sadness (leaving).

Beyond Speech Alone – Produced by Scope this booklet and DVD provides guidelines for practitioners providing counselling services to clients with complex communication needs associated with a disability. This resource is not free.

Making information accessible

Providing information that is accessible to an individual allows them to participate in making decisions about their mental health care. The most appropriate format will differ depending on the person’s needs.

For people with intellectual disability, the provision of Easy Read information is recognised as an important form of accessibility. Easy Read materials adapt standard information into a briefer copy, which contains only the main points of information and pictures to assist with comprehension.

The resources are designed for professionals to use with individuals. While some people may prefer to be provided with the resources to read independently, others will need support to understand the information. A Toolkit by 3DN is also available with more detailed information on supporting people to make information accessible and to use Easy Read well.

Similarly, plain English involves writing clearly so readers can find, understand, and use the information they need. Both Easy Read and plain English use simplified language, grammar, font, and key headings and bullet lists. However, plain English has more text, less white space, and relies less on the use of images. Scope Australia’s guide and the NSW Government’s resource on how to write in plain English have more detailed information on supporting people to make information accessible.

- Whittle EL, Fisher KR, Reppermund S, Lenroot R, and Trollor J. Barriers and Enablers to Accessing Mental Health Services for People With Intellectual Disability: A Scoping Review. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2018;11(1): 69-102.