Assessment and diagnosis

Jump to a section below

Key points

- It is important to take a longitudinal approach to assessment.

- Consider how you can meet the communication, sensory and physical needs of the person with intellectual disability during the assessment process.

- Establish baseline functioning to gain a better perspective on the presenting problems.

- Behavioural changes can be a result of mental or physical health.

- Seek collateral information from carers, family, support workers and health and disability professionals.

- Standard diagnosis criteria may not consider atypical or behavioural manifestations of mental illness for people with intellectual disability.

- Tentative or provisional diagnoses may be required, and diagnosis is often an ongoing process.

This section provides key information around working with people with intellectual disability during the assessment and diagnosis stage. Assessments are caried out to i) gather information to inform the problem formulation, diagnosis, and care plan ii) build rapport with the person (which is particularly important for people with intellectual disability and can take longer), and iii) record information to create a baseline to assess the impact of any interventions. The assessment findings inform the diagnosis (or provisional diagnosis), treatment approaches, behaviour support plans, and applications for additional support. Considerations for specific service types are provided at the end.

You may also like to view 3DN's Intellectual Disability Health Education course Assessment of Mental Disorders in Intellectual Disability for a small fee or which is available free of charge for NSW Health professionals through My Health Learning on HETI.

Below are key considerations and key questions you may have when working with people with intellectual disability during the assessment and diagnosis stage.

For a list of specialist health services for people with intellectual disability see Specialist intellectual disability services.

Assessment

Assessment – Key considerations

Meeting the needs of people with intellectual disability before and during mental health assessments

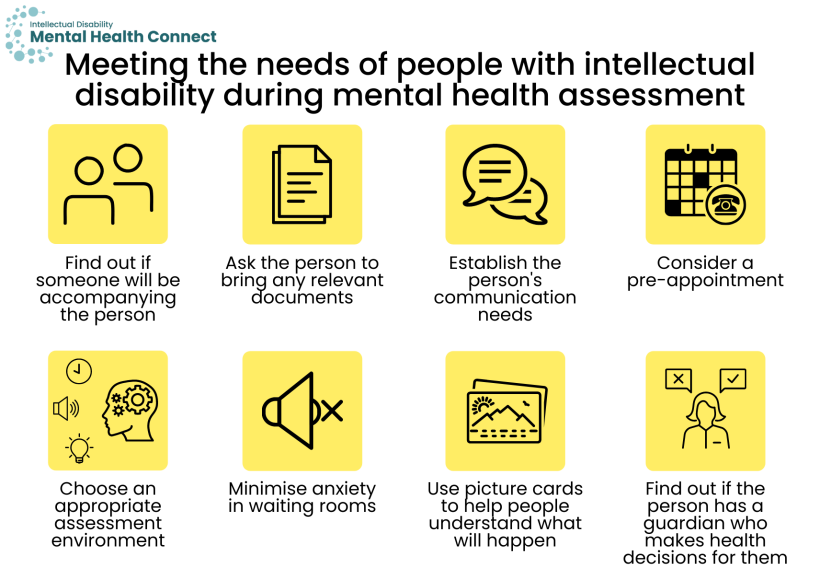

There are several key considerations before and during an assessment to ensure the needs of people with intellectual disability are met.

First and foremost is to take a longitudinal approach to assessment. More time is required as information generally needs to be gathered from multiple sources (i.e. the individual, their support networks, other health, and disability professionals). Additional key considerations are below.

- Find out if someone will be accompanying the person to their appointment and their relationship to the person.

- Ask the person with intellectual disability or the person who will be accompanying them to bring the results of any relevant assessments/reports, monitoring charts, and behaviour support plans.

- Establish the person’s communication needs and ensure information is accessible. See the Communication section for more information. See 3DN’s Making mental health information accessible for people with intellectual disability – A Toolkit for more information.

- A pre-appointment may be beneficial to i) meet the person and show them around the e.g. clinic/office to help reduce anxiety and ii) understand more about the person’s strengths to utilise in a strengths-based approach.

- Choose an appropriate assessment environment where possible that addresses the person’s physical and sensory needs.

- Many people with intellectual disability experience anxiety in waiting rooms. Suggest booking an appointment at a time when there is less likely to be a wait and endeavour to be on time. Ensure there is a quiet space for the person to wait rather than a busy waiting room. You could also let them know they can wait outside or in the car and you will call them when ready.

- Picture cards can be used to help people understand what will happen when they receive support for their mental health, for example i) professionals they will see and what they do, ii) the physical environment e.g. waiting room, treatments, and iii) routine for people in inpatient settings (e.g. mealtimes/bedtime).

- If not already determined from the Intake stage, find out if the individual has a guardian or person responsible who makes health decisions for them and gather their contact details. Continue to assess capacity to consent and promote supported decision-making. See the NSW Trustee & Guardian website and their Capacity Toolkit. There is also more information in 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit (page 29) and Intellectual Disability Health Education course Consent, Decision-Making and Privacy – A Guide for Clinicians.

Assessment – Key questions

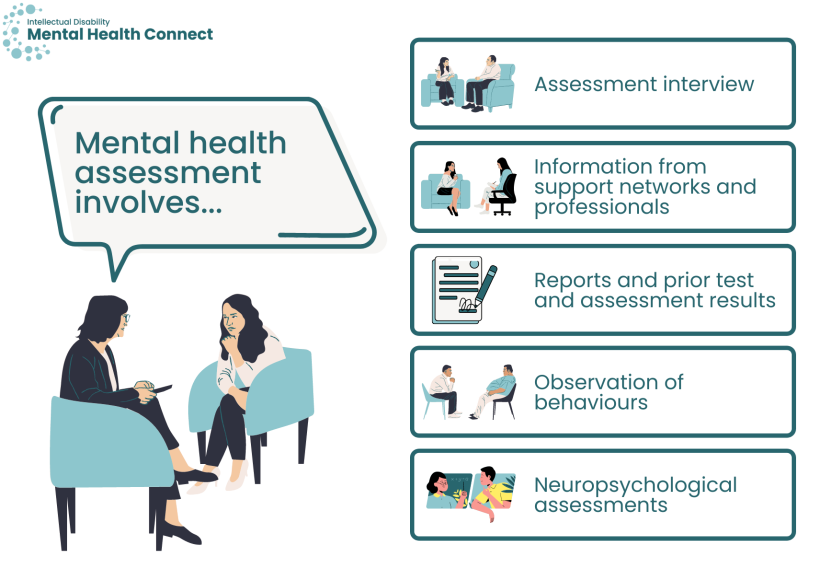

Many components of an assessment for people with intellectual disability are similar to those of the general population. However, more emphasis may be put on gathering a thorough developmental history, assessing behaviour changes, and gathering information from informants. When enquiring about information that has been collected, where possible determine who it was collected by and when. This will help you to decide its relevance to the person’s current situation and if it remains accurate at the time of assessment.

Assessment components particularly important to consider for people with intellectual disability include the following. Also see the Intake section; some information listed may be gathered during the assessment stage for some services.

Assessment interview

The presenting problem and baseline functioning

- Why the person is seeking an assessment and what they think may be the problem/what may be causing it. Does the presenting problem vary across different contexts?

- Assessment of baseline functioning. Baseline, or normal, functioning and behaviour for people with intellectual disability varies greatly between individuals.

- To assess baseline functioning, questions can include i) what the person needed help with, and what they did independently before symptoms started, ii) examples of things they enjoyed, iii) if changes in their mood, functioning and behaviour were sudden or more gradual, and when they began, and iv) if there were any changes in their life at that time.

- The Wellbeing Record can be used by carers and supporters to record a person’s baseline wellbeing and any changes that occur. This can assist health professionals to gain a broader understanding of what is typical for the person and what any changes in behaviour or mood may indicate.

Comprehensive biopsychosocial history

- Current physical health including pain, and past history.

- Current and past medication use including psychotropics.

- Note: A Webster pack alone may not provide you with all of the information as the person may also receive other medications via injections, creams, inhalers etc.

- Has the person sought treatment for their mental health before? What worked/what did not work (including informal supports)? Do they have a current mental health treatment or care plan?

- Developmental history

- Establish the cause of the person’s intellectual disability if possible. Certain syndromes that cause intellectual disability are associated with particular psychiatric or medical disorders e.g. Fragile-X syndrome is associated with anxiety and hyperactivity. Certain genetic disorders that cause intellectual disability are associated with distinct behavioural patterns known as behavioural phenotypes. An awareness of these associations can assist with interpreting signs and symptoms.

- Functional abilities and adaptive behaviour

- Current life situation including:

- supports

- living situation

- stressors, and

- any recent changes (change in activities, routine, change in staff, grief etc).

- Psychosocial history including:

- significant life events

- history of trauma (see the section on working with People who have experienced trauma)

- educational and cultural history, and

- strengths that can be utilised in interventions.

Current supports

- Is the person an NDIS participant? If so, seek a copy of their plan/list of services, past and present.

- Does the individual have a behaviour support plan? When was this plan developed/last updated? How is it currently being implemented? What impact is the behaviour support plan having?

Information from support networks and professionals

- Collect collateral, or informant, information from e.g. carers, family, friends, paid and unpaid support workers, and other health and disability professionals (with appropriate consent).

Reports and prior test and assessment results

- Collect any reports/results not provided during the intake stage e.g. reports from specialists and other professionals e.g. occupational therapists, medication charts, and neuropsychological assessment results.

Observation of behaviours

- Take the time to observe the person. Do they present the same in different environments e.g. at home versus a clinic and with different people e.g. a parent versus a carer?

- Observational records such as sleep, weight, and ABC (Antecedent, Behaviour, Consequence) or STAR (Setting, Trigger, Action, Response) style charts can be used by support networks to observe behaviour and share with professionals. See these examples of ABC and STAR charts (page 5) that can be used to help develop charts tailored to the observer’s role (e.g. family member, support worker etc).

- Ask support persons whether certain behaviours are typical for the person, and if not, i) when they started or increased in intensity, and ii) what they could signal (they may be able to provide details on what the person is trying to communicate). Ask supporters to complete a Wellbeing Record to gain a better understanding of the person’s behaviours and changes.

- Undertake a comprehensive assessment of any behaviours of concern, collaborating with support persons and disability services to evaluate the relative contribution of mental and physical health, environment, communication, and stressors on behaviour through methods including clinical interview, informant questionnaires, psychometric measures, and observation. For more information on what changes in behaviour could mean, see Why has a person’s behaviour changed below.

Neuropsychological assessments

- Consider referring a person with intellectual disability for a neuropsychological assessment if they have never had one, or a significant amount of time has passed since their last assessment. [1] An assessment of cognitive functioning can help understanding of the person’s verbal and practical abilities, strengths, and support needs. It can also help with early identification of dementia, which can have an earlier onset in people with intellectual disability. There is more information in the Transfers of care section around how to plan for the risk of early onset dementia in people with intellectual disability.

- Referrals can be made to a clinical neuropsychologist or clinical psychologist in LHD/SHNs where available or privately. University psychology clinics also provide neuropsychological assessments, for example the Neuropsychology Clinic at Macquarie University. Contact a clinic to discuss whether they would be suitable for the person you are seeing.

- The Statewide Intellectual Disability Mental Health Outreach Service team also includes a neuropsychologist who can provide specialist advice and consultation.

Some psychometric tests have been developed or adapted for use with people with intellectual disability. Some are for use with the person directly to assess subjective internal states, while some are to assess objective behavioural observations made by a member of their support network. Some examples include:

- Moss Psychiatric Assessment Schedule (Moss-PAS) A suite of mental health assessments for people with intellectual disability that includes clinical interviews (to be administered by specially trained mental health professionals) and a checklist that can be used as a screening tool by support networks and mental health professionals.

- Depression in adults with intellectual disability – Checklist for carers A checklist for carers to record possible depressive symptoms in people with moderate – profound intellectual disability to assist GP consultations.

- Developmental Behaviour Checklist (DBC) [2] A suite of instructions for the assessment of behavioural and emotional problems of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. It is completed by parents or other primary carers or teachers.

For more assessment tools, see this Assessment tool list.

Support network members (carers, family, formally appointed guardians, friends, support workers, and advocates) are often involved in either requesting an assessment or providing information. They will often accompany the individual to their appointments. Still speak directly to the person with intellectual disability in the first instance, not their support person who has accompanied them. Consider the following to work effectively with support networks.

- If a support person has made the appointment but is unable to attend, contact them beforehand to discuss their reasons for concern and ask if there is another individual who knows the person well who could attend the appointment. This will increase the chance of obtaining all relevant information. [1]

- Sometimes the person supporting the person with intellectual disability to attend the assessment may not know them very well (e.g. a new support worker). In this case, ask if there are family members or other individuals who may be able to provide additional information.

- Check with the person i) if you can ask their supporter about them, ii) whether they agree with what their supporter has said, and iii) whether they would like to speak with you alone.

- Take note of how supporters interact with the person with intellectual disability and use similar techniques if appropriate, for example communication techniques and how they explain concepts.

- Consider the support person’s situation and their needs, for example their expertise and capacity to assist with any implementation and monitoring of care plans, and if they require any support themselves.

As described in the Intake stage section, you can consult with colleagues, specialist professionals and specialist intellectual disability teams; see more information here. They can offer advice on assessment processes, meeting the person’s needs during assessment, assessment tools, co-ordinating multidisciplinary assessments, and referral for e.g. neuropsychological assessments.

At the assessment stage the Statewide Intellectual Disability Mental Health Outreach Service can offer:

- advice on referral pathways and resources if it is identified that further support is required from the assessment

- case-based discussions with a Hub psychiatrist and referring doctor, or Hub allied health clinician and treating allied health clinician to discuss assessment approach or findings

- clinical consultation with the person with intellectual disability and family/support network to determine presenting problems and interpretation with advice to referrer

- joint assessment with the referrer, person with intellectual disability, and family/support network

- capacity building and professional development opportunities to assist mental health professionals conduct comprehensive assessments for complex cases.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis – Key considerations

Diagnostic criteria and differences for people with intellectual disability

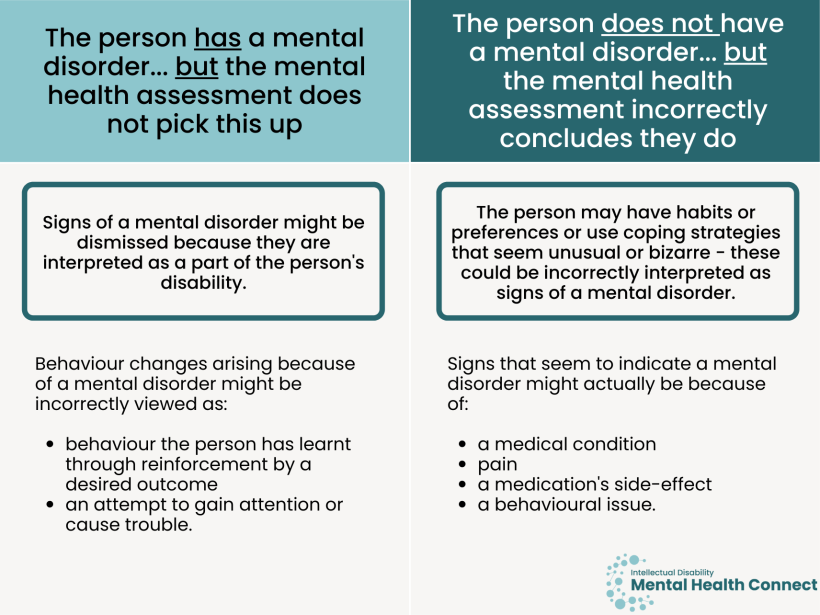

Diagnosis for people with intellectual disability can be more challenging as i) their baseline functioning is more likely to be unique, ii) symptoms of mental illness are more likely to be behavioural or atypical, and iii) they are more likely to be experiencing challenges in various domains. Consider the following points with regard to diagnostic criteria.

- Standard diagnostic criteria that rely on people verbally reporting symptoms can be used by people with a mild level of intellectual disability who have relatively well developed communication skills. [3]

- Standard diagnostic criteria i) do not consider atypical symptoms or behavioural manifestations of mental illness in people with intellectual disability, ii) may assume a certain level of development in e.g. social functioning which cannot be assumed for people with intellectual disability, and iii) may not be valid for people with severe intellectual disability, communication impairments or those who have an autism spectrum disorder.

- The Diagnostic Manual – Intellectual Disability 2 (DM-ID 2) and the Diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders for use with adults with learning disabilities (DC-LD) [4] have adapted the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria respectively for people with intellectual disability.

- Consider ways that the subjective experience of a mental illness may be expressed differently in someone with intellectual disability.

- A diagnosis should consider that behaviour and cognitions that are thought to be due to mental illness may in fact be caused by pain, physical illness, medication side effects, stress, or are normal idiosyncratic behaviours or cognitions for that person.

- Provide feedback to the person with intellectual disability and their support networks on the assessment findings and possible or provisional diagnosis in an accessible way for all parties. Seek their thoughts on your interpretations and take these into consideration. Explain the reasoning for only providing a provisional diagnosis if applicable, and whether further assessment will take place.

Diagnosis – Key questions

Behaviour change or behaviours of concern can be a presentation of mental or physical ill-health. It is important that behaviours of concern, especially those that are not typical for the person, be investigated and not assumed to be due to the person’s disability.

- People with more severe intellectual disability who have communication difficulties can present with atypical mental health symptoms, often manifesting behaviourally. [5, 6] It is important to be familiar with diagnostic overshadowing, whereby symptoms of mental ill health are misattributed to the intellectual disability rather than a manifestation of a mental disorder. [7]

- Behavioural changes can have physical causes such as pain, constipation, urinary tract infections, toothache or earache which cause distress and agitation. People with intellectual disability often do not, or cannot, tell others (including family) that they are in pain or have an injury.

- It can be complex to determine the cause of behavioural changes or behaviours of concern. Symptoms can be similar e.g. anhedonia, sleep disturbance, decreased food intake, social isolation could indicate depression or toothache. Investigation, including consulting with third parties, is required for differential diagnosis.

- Other causes can include environment or sensory issues and life circumstances e.g. housing issues, bullying, issues with other residents or staff in group homes, or loss of services.

- It should never be assumed that a person’s behaviours of concern are ‘learned’, a bad habit, or an attempt to seek attention.

- If no obvious physical or mental health cause can be found, consult the individual’s behaviour support plan recommendations and de-escalation techniques (or encourage the creation of a plan if the individual does not have one) and work with support network members to implement/refine techniques.

This is common when working with people with intellectual disability. It is OK to maintain a tentative or “provisional” diagnosis. [1] If you are unsure of a diagnosis, you can:

- collect further information from different sources or third parties

- assess the person in a different environment such as their home

- repeat the assessment if appropriate (e.g. the person was tired or unwell)

- communicate with the person with intellectual disability and support networks about the preliminary outcome of the assessment. Ask what they think about this feedback.

- consult with a colleague who has experience in intellectual disability mental health or a specialist intellectual disability mental health team

- If the nature of the presentation is particularly complex and assistance is required in determining a diagnosis, specialist services such as the Statewide Intellectual Disability Mental Health Outreach Service can assist with i) case review and specialist opinion on complex cases, ii) ambiguous presentations or iii) differential diagnosis. See more information about specialist intellectual disability mental health services.

- conduct regular reviews and reconsider diagnostic possibilities over time as more information is gathered.

Sometimes there may be disagreement between clinicians, or between a clinician and the person with intellectual disability/their support networks around a diagnosis, treatment, or transfer of care decision. If this situation arises, there are steps that you can take. These are outlined in detail in the Clinical stalemates section. In summary these can include:

- seeking advice from colleagues, specialist, and tertiary services such as Specialist Intellectual Disability Health Teams and the Statewide Intellectual Disability Mental Health Outreach Service

- using adapted assessment and diagnostic tools such as the DM-ID 2

- seeking to understand reasons for not agreeing with the diagnosis or treatment approach e.g. the diagnosis and subsequent treatment approach did not lead to a positive response in the past

- treating a diagnosis as a ‘working hypothesis’ and gathering further assessment information/monitoring treatment response and reviewing regularly

- considering convening a multidisciplinary, multi-agency complex case review.

Considerations for specific services

- Consider use of the Comprehensive Health Assessment Program (CHAP). The CHAP was developed to help identify and document the often complex physical and mental health needs of people with intellectual disability to support screening and prevention measures. It documents the person’s health history and provides prompts and guidelines for GPs.

- Key considerations and actions after assessing a person with intellectual disability’s mental health

- People with intellectual disability and their support networks tell us that choice and time to consider options is very important. When referring to specialists or allied health professionals, GPs could provide details of several suitable professionals (e.g. location of their office, image of the professional if available) so the individual can consider their options and determine who they will be most comfortable seeing. It is important to record these options in a way that is accessible to the person so that they can think about them after meeting with you.

- It is helpful to develop knowledge of local supports, psychiatrists and allied health professionals with experience or an interest in intellectual disability mental health, and local community supports. People with intellectual disability and their support networks tell us a lack of knowledge of suitable local professionals and supports is a significant barrier to accessing quality mental health care. They often seek this information first from their GP.

- GPs can help people with intellectual disability and their support networks to know what to expect when seeing a new professional such as a psychologist for the first time e.g. what the purpose is, how to prepare for their visit, preparing and writing down what the person would like to say.

- To help address known barriers to accessing services for people with intellectual disability, GPs could contact the professional or service they have referred the person to explaining the reason for referral and why it is important for the person to be seen promptly (especially if urgent or waiting lists are long).

- Follow-up after the person has had their initial appointment with a specialist or allied health professional to ask i) how the appointment went, ii) if they liked the professional, and iii) if another referral is needed. Let the person know it is OK to say they would like to see a different professional.

- How GPs can equip themselves to facilitate these considerations

- It can take time to build up local knowledge of professionals who have experience and expertise in intellectual disability mental health. Ask colleagues, people with intellectual disability and their support networks, and specialist intellectual disability mental health services such as the Statewide Intellectual Disability Mental Health Outreach Service for recommendations in your local area.

- Reach out to local professionals and services to ask about their experience working with people with intellectual disability and how they meet their needs.

- If an individual has arrived with no documentation or information, determine if there is someone you can call to find out more about their presenting issue and medical history. If they have come with e.g. a support worker, encourage them to bring a summary of the person’s health history e.g. the Admission2Discharge (A2D) Together Folder or the Council for Intellectual Disability’s My Health Matters folder, if the need to attend the emergency department in future.

- Where possible, assess the individual in a quiet location/individual room.

- Explain to the person and any support person who has accompanied them that what can be achieved in an emergency setting is limited (i.e. that they cannot do a comprehensive assessment). However, assure them that you will ask questions to determine the best course of action to assist them/keep them safe today, and recommend who they can see for a more comprehensive assessment.

- After an assessment has been conducted, discuss with the person with intellectual disability and support persons your understanding of their situation and check whether they agree with your interpretations.

- Also see the Intake, Treatment and Transfers of care sections for more information around providing care for people with intellectual disability in emergency departments.

- More detailed documentation of medications on admission may be required, in addition to a history of medications trialled and previous response.

- Pathways to Community Living Initiative (PCLI) can be involved on acute admissions to work with clinical staff and service providers to create a better chance of a successful transition back to the community. Ideally, they would stay involved for a few months post-discharge to prevent re-admission.

- Communicate the findings of the assessment and implications to the person in an accessible way (e.g. via Easy Read). It is best to have a member of the person’s support network present when this is discussed. However, if this is not possible or the person does not have someone appropriate, ensuring accessibility of the information is particularly important in an inpatient setting.

- Explain in an accessible way what any proposed treatments or interventions would involve and the benefits and risks. Seek the person’s thoughts and wishes on any proposed treatments, even if they are an involuntary patient. Provide them with an opportunity to ask questions. Employ supported decision-making and seek informed consent from the individual or a person responsible where applicable.

Resources

- See a list developed by 3DN of assessment tools suitable for use with people with intellectual disability.

- The Council for Intellectual Disability has checklists that help guide health professionals and administrative staff through reasonable adjustments they can offer before, during and after a health appointment to ensure they are accessible to people with intellectual disability. The checklists include links to Easy Read templates such as appointment letters and referrals.

- 3DN's Intellectual Disability Health Education course Assessment of Mental Disorders in Intellectual Disability

- Tools to assess baseline functioning such as the Wellbeing Record which can be used by carers and supporters to record a person’s baseline wellbeing and any changes that occur.

- Tools to record a person’s health history

- Council for Intellectual Disability’s My Health Matters folder.

- Admission 2 Discharge A2D Together Folder

- The Diagnostic Manual – Intellectual Disability 2 (DM-ID 2) provides diagnostic criteria of mental disorders for people with intellectual disability to facilitate accurate diagnosis.

- The Society for the Study of Behavioural Phenotypes has a series of Syndrome Sheets with information on genetic, cognitive and behavioural aspects of different syndromes that can cause intellectual disability.

- For information on supported decision-making and capacity to consent see

- Fletcher RJ, Loschen E, and Stavrakaki C, DM-ID: diagnostic manual-intellectual disability: a textbook of diagnosis of mental disorders in persons with intellectual disability. 2007, Kingston, NY: National Assn for the Dually Diagnosed in association with the APA.

- Einfeld SL and Tonge BJ, Manual for the Developmental Behaviour Checklist: Primary Carer Version (DBC-P) & Teacher Version (DBC-T) (2nd ed.). 2002, Clayton, Melbourne: Monash University Centre for Developmental Psychiatry and Psychology.

- Therapeutic Guidelines Limited, Management guidelines: developmental disability. Version 3. 2012, Therapeutic Guidelines Limited: Melbourne.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists, DC-LD (Diagnostic Criteria for Psychiatric Disorders for Use with Adults with Learning Disabilities/Mental Retardation). 2001, London: Gaskell.

- Moss S, Emerson E, Bouras N, and Holland A. Mental disorders and problematic behaviours in people with intellectual disability: future directions for research. Journal of intellectual disability research : JIDR. 1997;41 ( Pt 6): 440-7.

- Fuller CG and Sabatino DA. Diagnosis and treatment considerations with comorbid developmentally disabled populations. Journal of clinical psychology. 1998;54(1): 1-10.

- Mason J and Scior K. ‘Diagnostic Overshadowing’ Amongst Clinicians Working with People with Intellectual Disabilities in the UK. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2004;17(2): 85-90.