Guiding principles

Jump to a section below

Key points

- The following principles inform professionals’ practice when working with people with intellectual disability:

- Rights

- Inclusion

- Person-centred care

- Independence

- Recovery-oriented practice

- Trauma-informed approach

- Evidence-based care

- There are a range of international, national, and state policies that outline priorities for providing quality health and mental health care to people with intellectual disability that can be used to underpin practice.

Guiding principles of care

Mental health care for people with intellectual disability must be underpinned by a human rights framework. This includes promoting inclusion and independence of people with intellectual disability, a person-centered approach, and recovery-oriented practices.

The Mental Health Statement of Rights and Responsibilities states that Australian governments have a responsibility to support the development of high quality, recovery-focused and evidence-based services. [1]

The following principles guide practice when working with people with intellectual disability. There is also more information on guiding principles in 3DN’s The Guide – Accessible Mental Health Services for People with an Intellectual Disability.

People with disability have a right to health and health care. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) [2] states that people with disability have a right to the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination. Australia has committed to the UNCRPD by ratifying it. Thus all professionals are required to uphold this right.

With regard to supporting people with intellectual disability and mental ill health, this means ensuring:

- the same range and quality of free or affordable mental health care available to those without an intellectual disability

- mental health services that address mental health conditions that are common for people with intellectual disability, and services that can assist in preventing secondary disabilities (e.g. depression as a result of social isolation)

- accessible mental health services that are provided as close as possible to the person’s own community, including in rural and remote areas

- professionals provide high quality mental health care and uphold ethical principles

- a system that prevents people with intellectual disability being denied mental health care and promotes high standards of mental health care.

Meeting the individual needs of people with intellectual disability can help to ensure they have equitable access to mental health care. You can assist by supporting people with intellectual disability to understand and exercise their rights.

It is important to note that all people receiving mental health care have the right to complain about their care and treatment. If a person’s rights have been violated under the Mental Health Act, complaints can be made to the Health Care Complaints Commission. Also see 3DN’s Easy Read guide on How to make a complaint about your mental health care, which can be provided to people with intellectual disability.

Resources on rights

- NSW Health’s Healthcare Rights bulletin.

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education course Equality in Mental Health Care – A Guide for Clinicians. This course can be accessed for a small fee or is available for free through My Health Learning on HETI for NSW Health staff members.

- For Easy Read information that can be provided to people with intellectual disability about their rights when obtaining mental health care, see 3DN’s resources on accessing mental health services in NSW.

People with intellectual disability have a right to fully participate in all aspects of community life. They should:

- be able to access all mental health services, including mainstream and specialised mental health services

- not be refused access to mental health services because of their intellectual disability, including programs aimed at preventing mental health problems.

To achieve this some people with intellectual disability will require support and accessible materials about mental health. Health professionals and services may need to adjust their approach through capacity development and fostering non-discriminatory beliefs and attitudes.

Mental health services can actively include carers, family members and support workers by supporting them to plan, implement and review care plans (unless this is against the wishes of the person with intellectual disability).

A person-centred approach maximises the person with intellectual disability’s involvement in decision-making about their mental health and care plan, rather than just being a passive recipient of care. The person-centred approach seeks to understand the situation from the person’s own perspective, discovering what is important to them, considering their age, community, and culture.

It is important to provide the person with intellectual disability with choices about their mental health care, in keeping with their age and capacity. While the person is the focus, consult carers and family where appropriate. Health and disability professionals are partners, working together with mental health professionals to provide person-centred mental health supports.

Resources on a person-centred approach

- NSW Health What is a person-centred approach?

- National Disability Practitioners resource What is a person-centred approach? factsheet

It is important to recognise the autonomy of people with intellectual disability and to maximise their independence, taking into account their age and capacity. Health and disability services must ensure that the supports offered to each individual promote as much independence as possible.

Supported decision-making and capacity to consent

An important component of promoting independence is supporting a person with intellectual disability to make decisions about their mental health care. This includes helping them to understand, consider, and communicate their choices. This is important when people are providing their consent for treatment.

Consider the person’s capacity to consent to decisions about their mental health. Determine if they have a guardian, or person responsible (see this and other NCAT fact sheets) who makes health decisions. Find out if they are supported to make some or all of their health decisions using supported decision-making. Supported decision-making involves supporting the person to make their own choices to the greatest extent. This could involve:

- choosing to discuss treatment options at an appropriate time (e.g. when they are not anxious)

- providing accessible information on the benefits and potential risks of each option

- giving them time to process the information and revisiting if required.

People’s capacity to consent can be situation-dependent and may change over time.

Resources on supported decision-making and capacity to consent

- NSW Trustee & Guardian website which includes a Capacity Toolkit.

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education course Consent, Decision-Making and Privacy – A Guide for Clinicians. This course can be accessed for a small fee or is available for free through My Health Learning on HETI for NSW Health staff members.

The National Standards for Mental Health Services state that recovery for individuals with mental ill health means “gaining and retaining hope, understanding of one’s abilities and disabilities, engagement in an active life, personal autonomy, social identity, meaning and purpose in life and a positive sense of self”. [3]

Recovery-oriented mental health practice aims to support people to build on their strengths so that they can take as much responsibility for their lives as possible at a given time. The person is seen as an expert in their own life and lived experience. Professionals can share their expertise.

For people with intellectual disability, recovery-oriented practice relates to their mental health, rather than their intellectual disability as such. Recovery-oriented mental health care moves the focus away from just treating mental health problems to more holistic care.

Recovery-oriented practice recognises that recovery outcomes include social participation and quality of life. The focus is on long term supports that promote ongoing wellbeing.

Health and disability professionals can work together with the person with intellectual disability and their support networks to provide recovery-oriented care. Working together makes sure that the support the person gets is consistent with their values and goals.

Resources on recovery-oriented care

- NSW Health What is a recovery oriented approach? page which includes resources

- healthdirect’s Recovery and mental health page

- South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust Easy Read Recovery plan

What is trauma-informed care?

Trauma-informed care is an essential part of recovery-oriented service provision. It is an approach whereby all aspects of a service are organised around recognising and acknowledging the prevalence of trauma, and being aware and sensitive to its dynamics. Trauma-informed care presumes that every person seeking treatment has been exposed to trauma. It requires an understanding that current service systems can re-traumatise individuals.

Trauma-informed care aims to minimise the impact of trauma and prevent re-traumatisation. It uses language and actions that make people feel safe, is collaborative and offers choice.

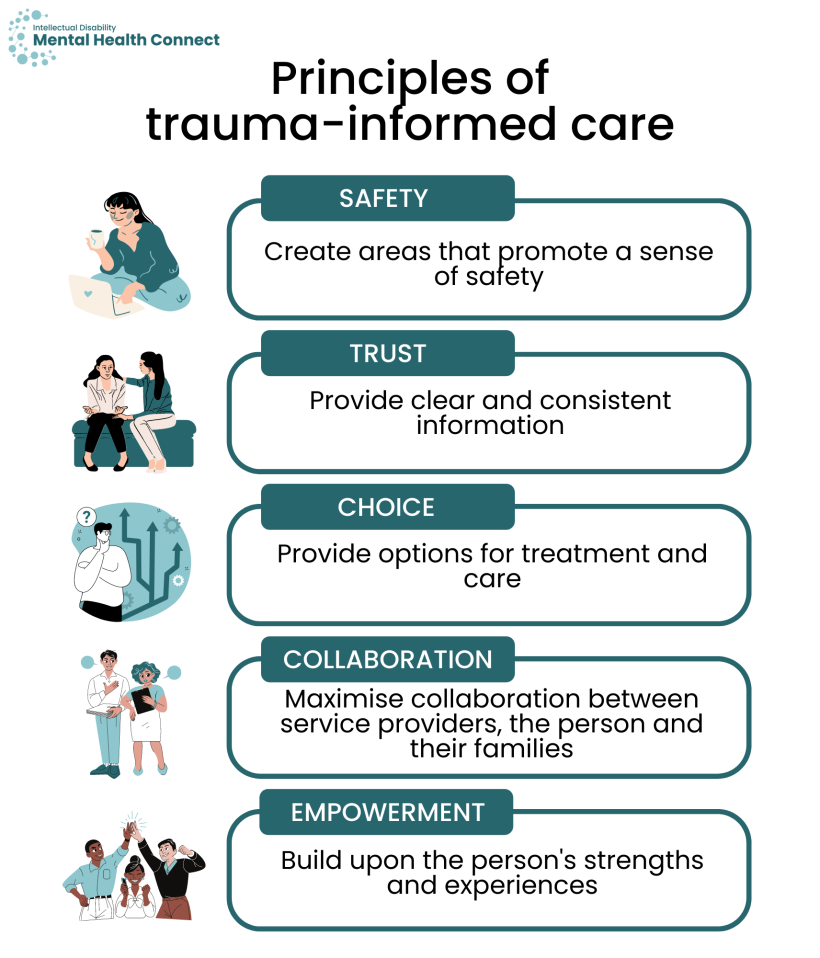

The key principles of trauma-informed care include:

- Safety: creating areas that promote a sense of safety

- Trust: providing clear and consistent information

- Choice: providing options for treatment and care

- Collaboration: maximising collaboration between service providers, the person and their families

- Empowerment: building upon a consumer’s strengths and experiences

Trauma-informed care and intellectual disability

Although there is limited research on the prevalence of trauma in people with intellectual disability, it is widely acknowledged in the literature that people with intellectual disability are more likely to experience traumatic or adverse life events, compared to people without intellectual disability. [4, 5]

People with intellectual disability are at increased risk of:

- physical and sexual abuse

- bullying

- adverse childhood experiences, including living with an adult with mental illness or alcohol abuse. [5-7]

This means that people with intellectual disability who are seeking services are likely to have trauma histories. Often, however, these trauma histories are undetected, and the person may not receive appropriate treatment for their trauma or be inadvertently re-traumatised by day-to-day practices or “treatment as usual”.

Painful or distressing health care experiences, especially if the person does not understand what is happening, can lead to resistance seeking health care in future. This fear can have lifelong consequences.

Following the key principles of trauma-informed care, below are some considerations to ensure that service provision for people with intellectual disability takes a trauma-informed approach.

Safety

- Ensure that the person feels safe in the environment in which services are being provided, especially inpatient services which can be distressing.

- Provide the person and their supporters with a point of contact who they can communicate with if feeling unsafe.

Trust

- Proactively build trust and rapport with the person.

- Ensure that there is consistency between communication and actions taken (e.g. seeing the person at their scheduled appointment time).

- Listen to the person’s support networks when they express concerns.

Choice

- Respect the person’s right to make choices and decisions, and facilitate their ability to have choice and control over decision-making by ensuring they are aware of all their options.

- Refusal of activities, treatments or services should not be viewed as non-compliance, but rather someone communicating their preference.

Collaboration

- Support people with intellectual disability as much as possible to be involved in planning using a person-centred approach.

- Collaborate with other services and professionals to ensure that all the person’s needs are met in a safe and appropriate way.

- Work with the person’s support networks.

Empowerment

- Provide the person with freedom of choice.

- Identify and acknowledge the person’s strengths and abilities and use a strengths-based approach.

- Consider alternative methods to meet the person’s needs and engage them in services and activities.

For more information see the Working with diverse groups section People who have experienced trauma.

Resources on trauma-informed care

- NSW Health information on trauma-informed care

- NSW Health’s Integrated Prevention and Response to Violence, Abuse and Neglect Framework has more information on trauma-informed care

- Trauma-informed care and practice organisational toolkit (TICPOT) – a resource for managers on how to develop a trauma-informed service and practice culture

- The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists’ position statement on trauma-informed practice

Make decisions informed by the best available evidence where possible. Ideally treatments should have been trialled with people with intellectual disability. However, this information is not always available. If there are no specific guidelines or information available, best practice can include interpreting results of studies in the general population. Mental health professionals can contribute by sharing new and innovative interventions they learn about or undertake within their networks.

Policy imperatives

There are international, national, and state imperatives for the provision of quality health and mental health care to people with intellectual disability including improved access to mainstream health care. These include:

International

National

- National Roadmap for Improving the Health of People with Intellectual Disability

- Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention plan

- Recommendations from the National Roundtable on the Mental Health of People with Intellectual Disability 2018

- National Preventive Health Strategy 2021-2030

- Australia's Disability Strategy 2021-2031

- The Australian Government’s Joint Standing Committee on the National Disability Insurance Scheme: NDIS Planning Final Report

- Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability – final report.

NSW

Resources

- NSW Health’s Healthcare Rights bulletin.

- The NSW Trustee & Guardian website for information on capacity to consent and supported decision-making in NSW including a Capacity Toolkit.

- The Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit for further information on informed consent and supported decision-making (page 29).

- 3DN’s The Guide – Accessible Mental Health Services for People with an Intellectual Disability which provides information about the roles and responsibilities of mental health service providers in delivering services for people with intellectual disability including guiding principles.

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education courses Equality in Mental Health Care – A Guide for Clinicians and Consent, Decision-Making and Privacy – A Guide for Clinicians.

- 3DN’s Easy Read resources on accessing mental health services in NSW that include information on people’s rights when obtaining mental health care including How to make a complaint about mental health care.

- The NSW Civil & Administrative Tribunal (NCAT) Guardianship Division’s ‘Person responsible’ fact sheet (see this and other NCAT fact sheets).

- Standing Council on Health, Mental health statement of rights and responsibilities. 2012, Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra.

- UN General Assembly, United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 13 December 2006, A/RES/61/106, Annex I. 2006, UN General Assembly: New York.

- Commonwealth of Australia, National Standards for Mental Health Services. 2010, Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra.

- Rich AJ, DiGregorio N, and Strassle C. Trauma-informed care in the context of intellectual and developmental disability services: Perceptions of service providers. J Intellect Disabil. 2020;25(4):603-18.

- Sullivan PM and Knutson JF. Maltreatment and disabilities: a population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(10): 1257-73.

- Austin A, Herrick H, Proescholdbell S, and Simmons J. Disability and Exposure to High Levels of Adverse Childhood Experiences: Effect on Health and Risk Behavior. N C Med J. 2016;77(1): 30-6.

- Byrne G. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of sexual abuse among individuals with an intellectual disability: A review of the recent literature. J Intellect Disabil. 2018;22(3): 294-310.