Transfers of care

Jump to a section below

Key points

- It is best if planning for discharge or transitions between services starts well in advance for people with intellectual disability to ensure appropriate supports are in place.

- Provide the discharge plan to the person with intellectual disability and all appropriate members of their support network in an accessible format to ensure all are aware of the plan and what to do if mental health deteriorates.

- People with intellectual disability often experience barriers when transitioning from child and adolescent to adult services due to differences in the service structure; there are actions that can facilitate access.

- A successful transfer of care can help to prevent admissions to emergency departments and inpatient units.

This section provides key information around planning for and supporting transfers of care, including at discharge and at times of transitions such as moving from child and adolescent to adult services.

People with intellectual disability and their support networks report that ongoing support is not available post-discharge. Providing support at this time is vital to supporting recovery and preventing re-admissions. Considerations for specific service types are provided at the end. You may also like to view the Transfer of Care section on page 37 of the Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit.

Below are key considerations and key questions you may have when working with people with intellectual disability before and after discharge and during transitions.

For a list of specialist health services for people with intellectual disability see Specialist intellectual disability services.

Discharge

Key considerations

Planning for discharge from hospital

Begin considering discharge needs early in admission. For people with intellectual disability who are at higher risk of harm in an inpatient service (such as from other patients, vicarious trauma, or increased medication usage to reduce stress caused by the admission and environment), consider pathways that will allow them to be discharged as soon as possible.

Create a discharge plan (or transfer of care plan) with the person with intellectual disability, their carers, family, support workers (especially if living in a group home or supported independent living), and multidisciplinary team. This may need to be a separate, more detailed plan than the standard transfer of care, or discharge, summary provided to all patients. Consider the following points when planning for discharge. You can also use our Planning for the discharge of a person with intellectual disability after a mental health admission – A planning tool.

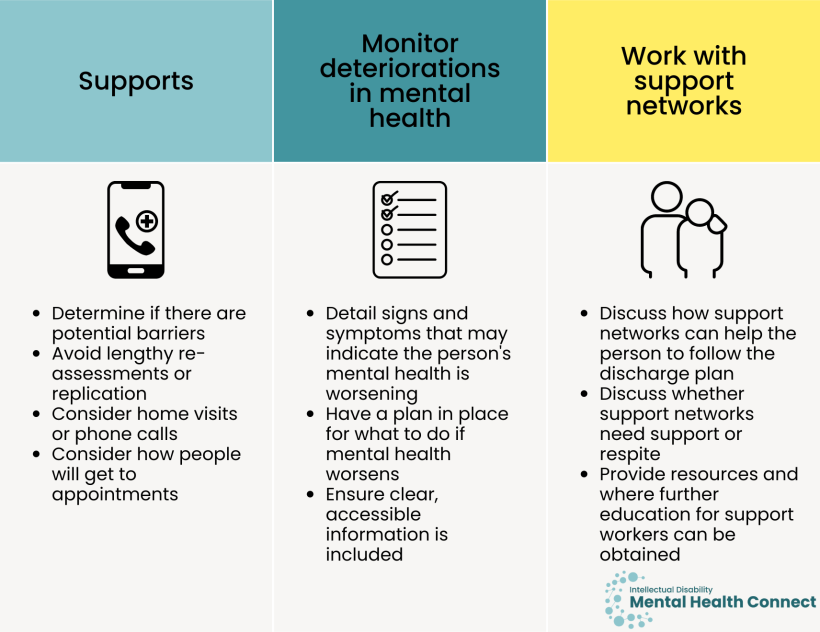

Supports

- Determine if there are potential barriers to discharge early so that supports can be put in place e.g. accommodation issues that would prevent discharge or NDIS funding not adequate to provide appropriate support on discharge. If the person has an NDIS package, their Support Coordinator or Local Area Coordination (LAC) can be contacted to discuss options.

- If providing a re-referral to a community mental health service or professional, avoid lengthy re-assessments or replication of the first referral pathway if it was not helpful.

- People with intellectual disability may face more challenges attending follow-up appointments than the general population (e.g. difficulties remembering appointments, lack of transport). Therefore, home visits or phone calls may be more suitable than clinic appointments.

- Consider how people will get to appointments. People with NDIS plans can be limited in the number of kilometres they can travel with support workers, thereby making it difficult to attend e.g. specialist appointments especially if they live in rural and remote areas. Consider this when suggesting referral options or investigate alternate transport options.

Monitoring deteriorations in mental health

- Detail signs and symptoms that may indicate the person’s mental health is worsening and the person should seek help from their GP/other services they are in contact with.

- Have a plan in place for what to do if the person’s mental health worsens and what to do in an emergency including information about after-hours services.

- Ensure clear, accessible information is included about what the person needs to do when they leave hospital, including:

- health professionals they need to see

- medication they need to take

- phone numbers they can call e.g., mental health team

- care for any physical health problems.

Working with support networks

- Discuss how support networks can help the person with intellectual disability to follow their discharge plan and monitor progress.

- Discuss whether carers and family members need support or whether respite may be beneficial.

- If support workers are concerned about managing behaviours of concern, provide resources and where further education can be obtained. For example, 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education has courses for disability professionals that can be accessed for a small fee or through a subscription purchased by their organisation.

Key questions

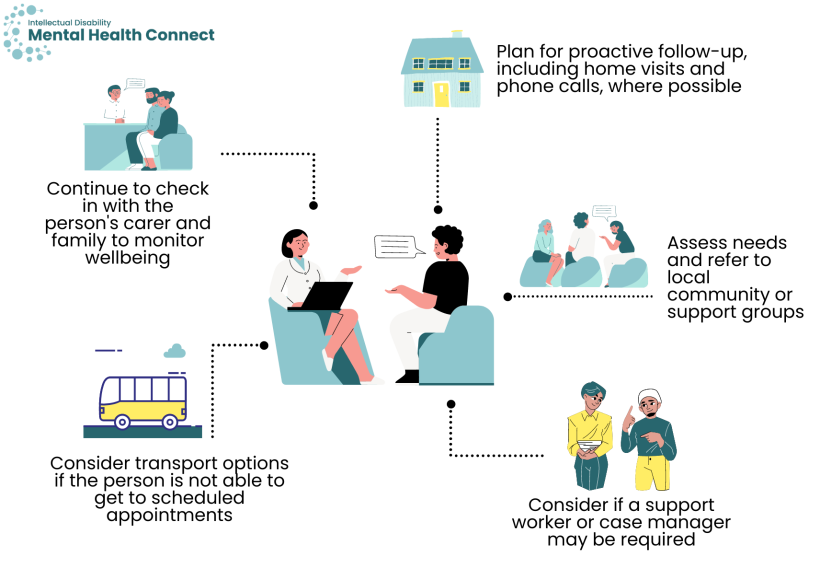

How can I best provide support post-discharge?

Discuss and provide the discharge plan to the person with intellectual disability in an accessible way (people often tell us that they have been provided with a discharge plan, but do not understand it). Ensure that the person’s support network, GP, and other professionals such as specialists and allied health professionals are provided with a copy of the plan. Also consider the following points.

- While follow-up is important for all patients, it is particularly important for people with intellectual disability due to their complex needs. Plan for proactive follow-up through outpatient services and community mental health teams, including home visits and phone calls where possible.

- During follow-ups, assess needs and suggest appropriate local community organisations or support groups in addition to referring to required health, disability, or social services.

- Consider if a support worker or case manager may be required if the person is having difficulty following their discharge plan, attending appointments, or managing with community care.

- If the person is not able to get to scheduled appointments, consider transport options e.g. community-based transport options or NDIS supports for transport.

- Continue to check in with the person’s carer and family to monitor their wellbeing and see if they require any additional supports e.g. a family liaison officer.

Considerations for specific services

When a person with intellectual disability finishes, for example, psychological therapy sessions with a professional or service in the community, a recovery plan and active follow-up is important. Develop an accessible plan with the person and their support networks, including:

- the person’s recovery goals

- plans for follow-up e.g. an appointment in two months, attend a local support group regularly

- how the person can continue to use and practise their coping strategies and skills

- signs to look for that may indicate mental health is deteriorating and clear steps of what to do

- how support networks can be involved in the recovery process.

Also see the Intake section for more information around providing care for people with intellectual disability within community mental health services.

- If the person with intellectual disability is safe to go home, provide appropriate referrals. If it is decided they need to be admitted, provide details of what will happen next.

- Let the person with intellectual disability and their supporters know what steps to take if their mental health worsens and what to do in a crisis.

- Inform the person’s GP that they have presented to the ED, including whether changes to medication are indicated and next steps for the person.

- If the person does not have a GP, encourage them to find one in their local area.

- People with intellectual disability can face challenges knowing where to find a GP or community mental health service and finding a service that is suitable for them. Staff in emergency departments may need to provide additional support when suggesting a person finds a GP or connects with community mental health services (especially someone who has presented multiple times). This may include:

- writing down steps for them e.g. how they could go about finding a GP (such as ask family and friends for recommendations, speak to their NDIS Support Coordinator, search via healthdirect’s resource Find a health service)

- writing down the contact details of a community mental health service and steps they can take next

- suggesting they view Where to start to get help within the I am a person with intellectual disability section of this website.

- Encourage carers, family, or support workers to develop an emergency department management plan if they do not already have one in case the person needs to attend an emergency department in future. This may include:

- a brief medical history

- medications list

- professionals involved in care

- behaviour support plan techniques

- considerations for the person (e.g. sensory requirements, their likes/dislikes, topics they like to talk about to help build rapport/reduce distress).

- If the person’s support worker has accompanied them to the emergency department, encourage them to support the person to follow-up with their GP/psychiatrist to discuss developing a crisis plan.

- Also see the Intake, Assessment and diagnosis, and Treatment sections for more information around providing care for people with intellectual disability in emergency departments.

Discharge resources

- Homelessness Australia – provides list of organisations that provide homelessness information and referral telephone services for those who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

- Intellectual Disability Mental Health Core Competency Framework Toolkit Transfer of Care section (page 37)

- 3DN’s Introduction to inpatient mental health services Easy Read Going home at the end of my stay in hospital template (clicking this link will download a word document). This template is to be modified by professionals before being provided to people with intellectual disability.

Transitions

There are several stages at which a transition of care may be required. These include:

- From child and adolescent to adult services

- From adult to older adult services

- Moving to a new location.

People with intellectual disability can also require psychosocial support when moving from school to work or further study. This can be a significant transition for any person with a disability, where people will often go from being supported in a structured, co-ordinated environment, to having challenges finding appropriate work or study. Times of change across the lifespan can cause significant stress, contributing to mental health declines.

Key considerations

A key transition stage for people with intellectual disability is moving from child and adolescent services to adult services. While children and young people with intellectual disability are generally connected with multidisciplinary teams who work closely together to provide care, adult services are fragmented, and equivalent services do not always exist.

- Successful transition is vital as it results in improved patient outcomes, less hospital admissions, and reduced acute and chronic complications. [1]

- The RACP Transition of Young People with Complex and Chronic Disability Needs from Paediatric to Adult Health Services position statement states that transition should be developmentally and culturally appropriate, holistic, multidisciplinary, and formally planned and co-ordinated.

People with intellectual disability and their support networks often voice concerns around what will happen when their parent carers are no longer able to care for them, in addition to what will happen when they become older adults themselves.

Genetic, biological, and psychosocial factors can lead to an increased risk of age-related disorders for people with intellectual disability including 4-5 times the risk of dementia, [2] and other health disorders such as diabetes and hypertension. [3] Thus, people may also have increasing needs for health and disability supports as they age.

Advance planning is crucial for people with intellectual disability, especially those with co-occurring mental ill health, given these times of transition can result in significant stress. Planning can also be carried out to address the risk of early onset dementia.

Key questions

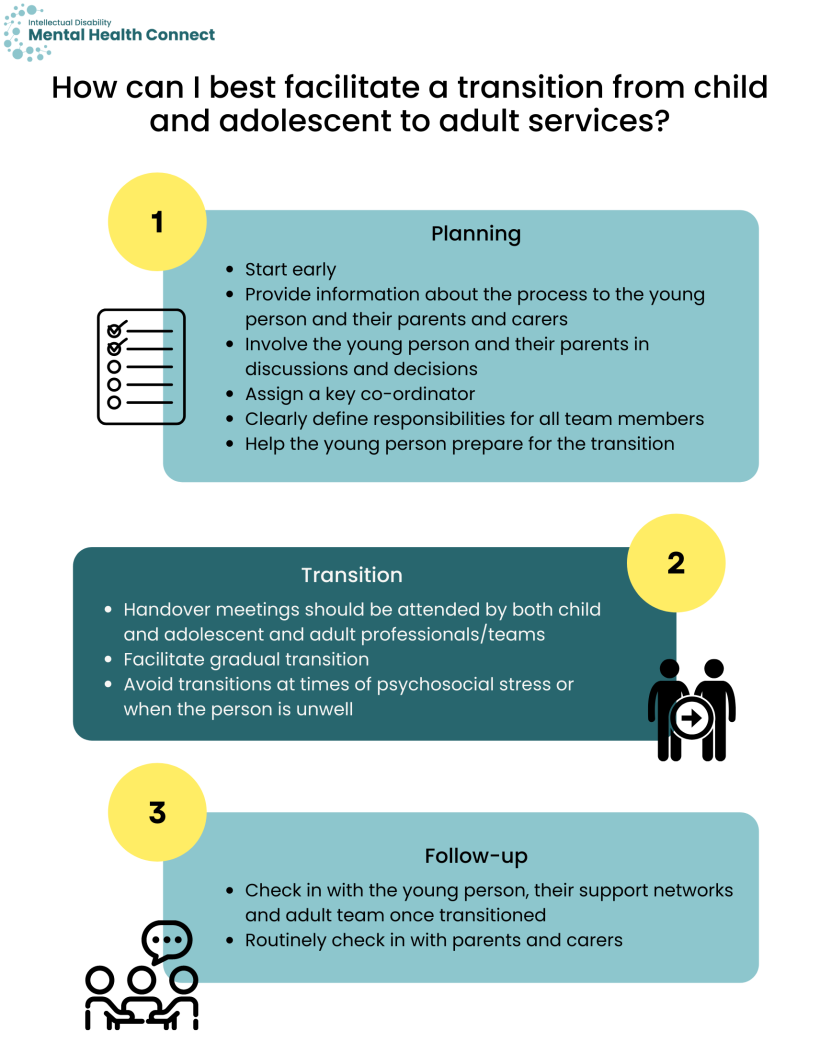

Consider the following at each stage of the transition process: [4, 5]

Planning

- Proactively start the transition process early so it is a continuous process and can be discussed during planned reviews; review potential risks early.

- Provide information about the transition process to the young person with intellectual disability, their parents, and carers.

- Involve the young person with intellectual disability and their parents in transition discussions and decisions; check that they agree with the plan.

- Assign a key co-ordinator who can provide case management and support to help the person with intellectual disability and their family through the transition process.

- Clearly define responsibilities for all multidisciplinary team members.

- Depending on the young person, help them prepare for the transition to adult services e.g. recording appointment times in their phone/diary, writing down what they would like to discuss/ask before the consultation, and starting to see their mental health professionals on their own if appropriate.

Transition

- It is best if handover meetings can be attended by both the child and adolescent and adult professionals/teams where possible.

- Facilitate gradual transition e.g. attending initial adult service appointments while still in contact with child and adolescent and adult service.

- Avoid transitions at times of psychosocial stress or when the person is physically unwell.

Follow-up

- Check in with the young person, their support networks and adult team once transitioned to the adult service.

- Routinely check in with parents and carers as to their support needs.

Discuss the following points with the person and their support networks as applicable. Discussion and planning will likely be an ongoing process over the long-term. Provide support and resources where required.

- Where people will live and how they will be supported when parent carers are no longer able to fulfil this role.

- How health, disability, and support needs will be met.

- Whether specialist mental health services are required e.g. Older People’s Mental Health (OPMH) services.

- Age-appropriate community activities and support groups (groups are often aimed at younger adults).

- Guardianship decisions.

- Making advance care directives.

- Support for siblings, who are often expected to take on caring responsibilities as parents age, and report stress in relationships if there are differences of opinion around approach. [6]

Planning can occur to address the risk of early onset dementia. See 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education course for health professionals, Dementia care for people with intellectual disability, and course for disability professionals, Supporting a Person with Intellectual Disability and Dementia that can be accessed for a small fee. Also see 3DN’s Dementia in people with Intellectual Disability: Guidelines for Australian GPs produced by the SAge-ID team.

- Risk factors for dementia in people with intellectual disability include:

- Down syndrome

- epilepsy

- sensory impairment

- poor mental health, especially depression

- poorer physical health

- undiagnosed health problems.

- Be attentive to early signs of dementia which can include:

- behavioural changes e.g. getting lost or misdirected, being confused in familiar situations

- memory problems

- challenges with gait and balance

- late onset seizures (or worsening of epilepsy)

- changes in personality.

- Arrange baseline cognitive testing if indicated.

- For people with intellectual disability with Down syndrome, it is suggested they:

- receive a comprehensive assessment at age 30-35

- reassess every two years in their 40s

- reassess every year from the age of 50 onwards. [7, 8]

- For people with intellectual disability from other causes:

- at age 40, ask questions regarding declines in function, changes in personality or behaviour, and cognitive slowing

- see the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices for information on their Early Detection and Screen for Dementia (NTG-EDSD).

- if concerns or changes are noted, refer the person to a psychologist or psychiatrist for a comprehensive assessment

- repeat the questions and screening every year from the age of 50 onwards.

- For people with intellectual disability with Down syndrome, it is suggested they:

Your responsibilities may include the following, depending on the individual.

- Identify suitable services for the individual to transition to.

- Co-ordinate and oversee the transition, not merely provide a referral.

- Work with the new service(s) to handover medical history, assessment results and other relevant information (with consent). This includes when a person with intellectual disability is changing GPs, or when a GP retires. Individuals often have a complex medical history, and handover is important to prevent the person having to provide a detailed medical history again, where details may be missed.

- Where appropriate, attend case conferences and joint appointments during the transition phase.

The following are known challenges when people are transitioning between services, particularly child and adolescent to adult services. Some ideas are provided as to how you can address these challenges.

- There are differences in child and adolescent and adult service models including eligibility, support intensity and service responsibility. Child and adolescent services are often well co-ordinated and multidisciplinary, whereas adult services are fragmented, accessed individually, and often only accessed in crisis. [4, 9]

- To manage these challenges, let the person with intellectual disability and their support networks know about these differences and what to expect, start planning early to ensure all health and disability services required are in place, and develop partnerships with services experienced in the care of people with intellectual disability in the local area.

- People with intellectual disability are required to have more autonomy and responsibility for their own health care when they transition to adult services which may be challenging for them.

- Begin discussions early with the young person and their family and support networks around what responsibilities they feel comfortable with. Gradually help to prepare the person well in advance of transitioning to adult services e.g. how to make appointments, attending some of the session alone.

- During and after the transition continually review, and if necessary, add additional supports if e.g. the person is missing appointments, not taking medication etc.

- The need to repeat medical history to a new network with no background knowledge of the person.

- Develop a personal health record outlining medical history, current mental health concerns and treatment, results from important investigations, and correspondence between professionals. Provide this to the new service during transition, supported by a verbal handover of key issues.

- Lack of continuity of care during transition.

- Developing multi-agency partnerships and streamlined pathways to facilitate transitions can help to ensure continuity of care. See Working with people with intellectual disability and their team for more details.

- Handover checklists can help to ensure all supports are in place and identify any barriers early.

- Active handover is vital.

- Maintaining follow-up for an agreed upon time can identify if a person has disengaged with services. If this occurs, organise a review session, identify barriers, and revise the transition plan including additional supports as required.

- Appropriate services with experience in intellectual disability mental health may be challenging to find.

- Seek assistance from professionals who specialise in intellectual disability mental health in your service, intellectual disability health and mental health teams, Clinical Nurse Consultants, or specialist intellectual disability mental health services on appropriate referral pathways and finding services in your local area. See more information on specialist intellectual disability mental health services.

Identifying and developing multi-agency partnerships between e.g. child and adolescent, and adult services within a local area can provide a clear pathway for people with intellectual disability to transition to appropriate services.

- Partnerships can provide awareness of services offered by different agencies, networking with professionals and knowledge of inter-agency eligibility criteria to ensure appropriate referrals.

- Greater co-ordination can be achieved if agencies agree on:

- referral protocols

- systems for transferring medical history and data, and record-keeping

- handover protocols e.g. joint planning meetings, joint sessions with the person with intellectual disability

- roles for all relevant individuals including the young person and their support networks

- communication methods

- methods to evaluate the transition partnership and protocols.

- Include young people, their support networks, clinicians, and managers in the development process.

For more information see the Working with people with intellectual disability and their team section.

Transitions resources

- RACP Transition of Young People with Complex and Chronic Disability Needs from Paediatric to Adult Health Services

- The National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices have information on their Early Detection and Screen for Dementia (NTG-EDSD)

- 3DN’s Intellectual Disability Health Education course for health professionals, Dementia care for people with intellectual disability, and course for disability professionals, Supporting a Person with Intellectual Disability and Dementia.

- 3DN’s Dementia in people with Intellectual Disability: Guidelines for Australian GPs produced by the SAge-ID team.

- NSW Trustee & Guardian on Guardianship decisions

- NSW Ministry of Health Making an Advance Care Directive guide

- Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, and McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Archives of disease in childhood. 2011;96(6): 548-53.

- Shooshtari S, Martens PJ, Burchill CA, Dik N, and Naghipur S. Prevalence of Depression and Dementia among Adults with Developmental Disabilities in Manitoba, Canada. Int J Family Med. 2011;2011: 319574.

- Sinai A, Bohnen I, and Strydom A. Older adults with intellectual disability. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2012;25: 359-64.

- Cvejic RC and Trollor JN. Transition to adult mental health services for young people with an intellectual disability. 2018;54(10): 1127-1130.

- Bhaumik S, Watson J, Barrett M, Raju B, Burton T, and Forte J. Transition for Teenagers With Intellectual Disability: Carers' Perspectives. Journal of Policy & Practice in Intellectual Disabilities. 2011;8(1): 53-61.

- Iacono T, Evans E, Davis A, Bhardwaj A, Turner B, Torr J, et al. Family caring of older adults with intellectual disability and coping according to loci of responsibility. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016;57: 170-180.

- British Psychological Society. Dementia and people with intellectual disabilities: Guidance on the assessment, diagnosis, interventions and support of people with intellectual disabilities who develop dementia. 2015. British Psychological Society Leicester, UK.

- Turk V, Dodd K, and Christmas M, Down's Syndrome and Dementia: Briefing for Commissioners. 2001, Mental Health Foundation.

- Kaehne A. Transition from children and adolescent to adult mental health services for young people with intellectual disabilities: a scoping study of service organisation problems. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities. 2011;5(1): 9-16.