Culturally and linguistically diverse people

Jump to a section below

‘Culturally and linguistically diverse’ (CALD) refers to the wide range of cultural groups that make up the Australian population and Australian communities. The term acknowledges that groups and individuals differ according to religion and spirituality, racial backgrounds and ethnicity, as well as language. [1] We acknowledge that all CALD communities, and people within these communities, are different and that the information on this page may not apply to all communities and people.

Key considerations

Intersectionality of identity and impact on mental health

People with intellectual disability from CALD communities can experience additional layers of disadvantage or discrimination. There may be an intersection of culture and other aspects of their identity that creates unique mental health needs, for example a person with intellectual disability who is from a CALD community and identifies as LGBTQ+. They may also experience a disadvantage in accessing culturally appropriate mental health services. This intersectional disadvantage may contribute negatively to their:

- help-seeking behaviour (e.g. they may be less likely to seek help outside of their immediate family)

- relationships with their family and community (e.g. family members and the broader CALD community may have different understandings of mental health and disability)

- overall mental health (e.g. they may be more likely to experience trauma).

Lower uptake of mental health services by people from CALD communities

Available data suggest that people from CALD communities are less likely to access mental health-related services funded by Medicare and mental health related medications subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule. [2] These data suggest that there is lower uptake of mental health services by people from CALD communities.

Given that people with intellectual disability face a large number of barriers to accessing appropriate mental health care (see the Accessible services section for more information), additional layers of disadvantage that may be experienced by people with intellectual disability from CALD communities further exacerbates these barriers.

Key challenges in meeting the mental health needs of people with intellectual disability from CALD communities

Within the general community, people with intellectual disability from CALD backgrounds may experience language issues, racism and stigmatisation in health care and community activities. They may also experience discrimination within their community. In some communities, there is stigma attached to having mental health problems and/or disability.

Discrimination within and outside CALD communities can lead to people with intellectual disability from CALD backgrounds to:

- seek services far away from their community areas, which can isolate people with intellectual disability and their families from their communities

- hide or deny their intellectual disability, mental health problems and true opinions or wishes regarding their intellectual disability or mental health. This can contribute to the inappropriate identification of the person’s needs (e.g. the person may receive intensive English language support rather than interventions like speech therapy)

- be reluctant to engage in formalised supports.

These can negatively impact on the mental health and experiences of people with intellectual disability in CALD communities.

Cultural responsiveness is a framework through which to improve service delivery to clients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Cultural responsiveness requires an organisation-wide approach to planning, implementing and evaluating services for clients of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. It is more than awareness of cultural differences, as it focuses on the capacity of the health system to improve health and wellbeing by integrating culture into the delivery of health services. [3] Some mental health services may not adequately cater to the needs of people with intellectual disability from CALD communities when providing mental health services. This may be due to a lack of awareness of:

- different cultures and languages

- how different cultures view mental health or intellectual disability

- expectations for family involvement in different cultures.

The lack of awareness can act as a barrier to care and may contribute to:

- poorer overall quality of mental health care

- a higher risk of errors or incidents that can lead to potentially serious clinical consequences

- the person and their family not accessing disability and mental health support services until a crisis point is reached.

In some cases, a lack of cultural and linguistic diversity within the service itself can affect whether culturally responsive care is provided. A lack of workplace diversity can mean that people from CALD communities may not seek out services because the service provider does not share the same first language. Mental health treatment outcomes could also be poor because information is not provided in a language that the person understands.

Some people with intellectual disability may have limited English and/or health literacy, leading to difficulties participating in the mental health system. These issues can be exacerbated for people with intellectual disability from CALD communities.

Language constraints can mean that people from CALD communities may not be able to access services, and some mental health professionals may not have experience working with interpreters. Similarly, interpreters may not have experience working with a person with intellectual disability. These issues can be compounded if sufficient time is not allocated by either the mental health professional or the interpreter for the appointment. Face-to-face interpreters are also becoming increasingly rare, meaning that people with intellectual disability with communication difficulties are not able to access interpreting services.

Poor health literacy can mean that people with intellectual disability may not know that they can access help for their mental health, or know how to describe their symptoms to mental health professionals. People with intellectual disability from CALD communities may also have a lack of familiarity with the mental health system in Australia, particularly if they were born overseas.

Family members may be unable to support the person if they have limited English or health literacy themselves.

Existing service protocols or, in some cases, the law may be in direct contrast to the person’s beliefs and preferences. For example, under Australian mental health and disability support systems, an individual needs to have a diagnosis to access professional supports and treatments. However, a person with intellectual disability and their family may not want a diagnosis due to differences in their socio-cultural conceptualisation of mental health and/or disability, or the implications of a formal diagnosis.

People from CALD communities or their family members may not trust government or public services, which can act as a barrier to accessing mental health care. Government distrust may stem from a history of distrust towards governments, or trauma suffered, in their country of origin.

There may also be privacy concerns, especially when third parties such as interpreters are involved. People from CALD communities may be concerned that confidential information may be shared with other members of their community, which can lead to stigma and discrimination.

How I can meet the mental health needs of people with intellectual disability from CALD communities

Meeting the mental health needs of people with intellectual disability from CALD communities requires the provision of holistic and empowering care by adapting your practice to be culturally responsive. By adopting culturally responsive practices, you can [4, 5]:

- increase the person’s access to mental health care and support services

- improve the effectiveness of the care received

- facilitate self-determination (e.g. decision-making)

- improve disparities in mental health outcomes

- contribute to shaping the mental health-related values, beliefs and behaviours of marginalised communities.

You can provide culturally responsive care by:

- listening attentively to and speaking clearly about concerns raised by the person and their support networks (e.g. concerns about negative staff attitudes, unfamiliar environments and cultural and linguistic differences)

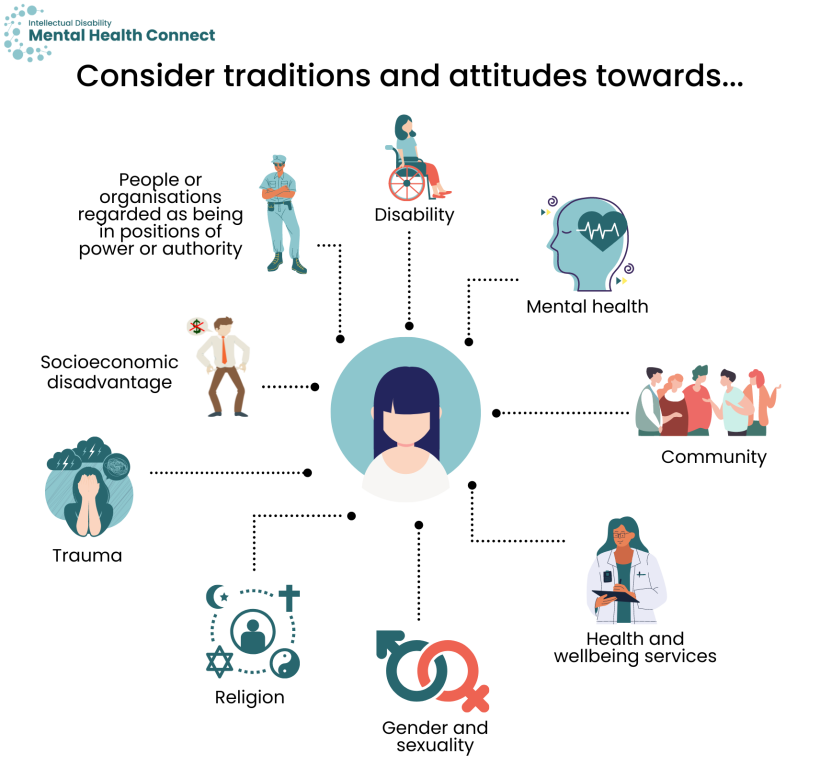

- considering the person’s traditions and attitudes. Some examples of things to consider are presented below.

- considering the expectations of family involvement in the person’s care, while asking the person’s individual preference about whether to include family members

- arranging interpreters in advance and working collaboratively with the interpreter

- providing written information in a language the person and their support networks can understand, if possible

- routinely including culturally responsive screening for trauma. You can read more about trauma and how to respond to trauma here

- using trauma-informed care. You can learn more about trauma-informed care here

- minimising power imbalances between professionals and the person with intellectual disability (e.g. removing the use of titles, engaging openly and transparently in a co-design fashion)

- facilitating the person’s access to housing, employment, health and other support services that are culturally responsive.

Consider the traditions and attitudes of individuals, their families and cultures, where relevant, towards:

- disability

- mental health

- community

- trauma

- gender and sexuality

- religion

- health and wellbeing services

- socioeconomic disadvantage

- people or organisations regarded as being in positions of power or authority.

Cultural competency describes the ability of individuals and services to work or respond effectively across cultures. Cultural competency can be built by engaging in cultural competency training programs. If there are certain ethnic minorities that are more prevalent in your area, it may be helpful to access cultural competency training specific to these groups.

Cultural competency may also be supported by getting involved in your local or relevant CALD community. There are many ways you can get involved, including:

- learning about how different cultures view intellectual disability and mental health

- getting involved in local community development events run by CALD community groups

- talking with community leaders

- raising awareness of how social conditions may be negatively affecting people with intellectual disability in these communities (e.g. stigma that associates disability with curses)

- partnering with local support services and advocacy groups

- connecting with the Multicultural Disability Advocacy Association of NSW

- using case studies and success stories to help motivate change

- being part of a larger social movement to create supportive environments for health.

There are many ways to achieve cultural competency but it is important to consult and involve the person, their family and available services whenever possible and appropriate.

Each person from a CALD community may have a different culturally determined perspective affecting their understanding, expectations and styles of communicating. [6] Consider whether further communication supports are needed. You can read more about adapting your communication here.

Some people from CALD communities may prefer a worker who speaks their language and understands their culture, while others may prefer someone outside their community. Some people may also prefer to be supported by a worker of a specific gender. If appropriate, involve family members and interpreters. If the interpreter is not a family member, it can be beneficial to have the same interpreter attend each session to support the development of short-hand and rapport between the interpreter and the person. Short-hand is a method of interpreting quickly by substituting different expressions without losing the message.

It is a NSW Health policy that professional interpreters, rather than family members, are used for health consultations. However, for other services, some people may request that their family member acts as their interpreter. If this is the case, you may still want to recommend to the person the use of a professional interpreter, as family members may be reluctant to pass on negative messages or may have a lack of understanding of medical terminology that could lead to inaccuracies in the interpretation.

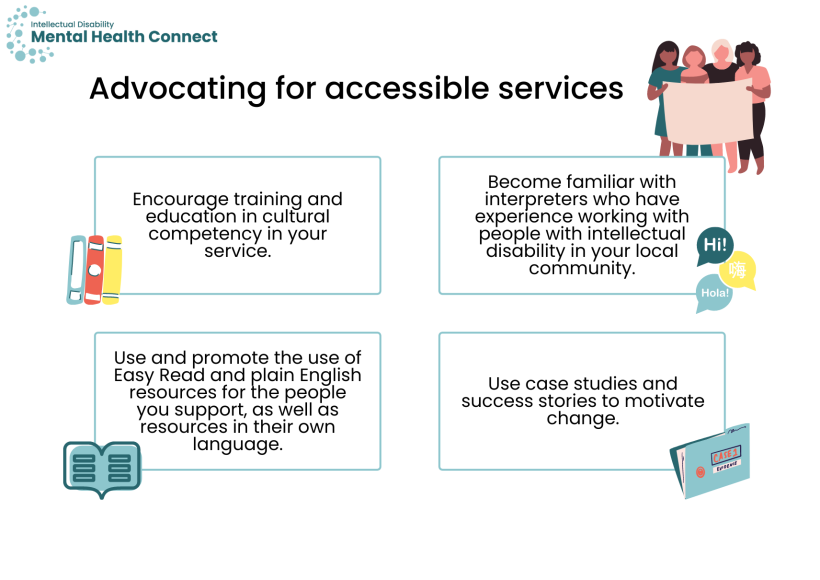

You can play an important role in advocating for accessible services for people with intellectual disability from CALD communities. For example, you could:

- encourage training and education in cultural competency within your service

- become familiar with interpreters who have experience working with people with intellectual disability in your local community

- use and promote the use of Easy Read and plain English resources for the people you support, as well as resources in their own language

- use case studies and success stories to help motivate change.

You can learn more about advocating for people with intellectual disability from CALD communities through the Multicultural Disability Advocacy Association and our information on how to advocate within the I am a person with intellectual disability section.

Key resources

Resources for providing culturally responsive mental health care

- eCALD is an e-learning course that focuses on the skills, behaviours and attitudes required for working with culturally, linguistically and religiously diverse groups. There is a specific training program for developing competence supporting people from CALD communities in a psychiatric context. eCALD was developed for the New Zealand context.

- NSW Health has information on how you can support a person from a CALD background with a mental health condition.

- The Transcultural Mental Health Centre has a cross-cultural mental health care resource kit for GPs and health professionals. The resource kit includes assessment tools, information and resources.

- Embrace Multicultural Mental Health provides mental health resources in a wide range of languages.

- The CLEAR Toolkit by Canada’s McGill University is a clinical decision aid developed to support health professionals to assess different aspects of the person’s vulnerability in a contextually appropriate and caring way. The toolkit is available in a range of different languages.

Resources for providing culturally responsive care

- The Centre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health provides:

- training in cultural competency

- a resource list to help you work with CALD communities and learn more about them.

- Speak My Language is a program that aims to ensure that people with disability from CALD communities have accessible and culturally appropriate information about their rights and choices. They are currently doing this by developing Easy Read materials in languages other than English.

- The Importance of Understanding CALD Demographics and Data Collection is a resource that looks at how professionals can capture the demographics of their potential consumers and compare these data to the numbers of the actual people accessing the service. The resource was developed for disability support providers but may be helpful for all professionals.

Translation and interpreter services

- The Translating and Interpreting Service offers interpreting services for non-English speakers. You can access immediate phone interpreting or pre-book a phone or on-site interpreter. You can call them on 131 450.

- NSW Health Care Interpreting Services provides free, confidential and professional interpreters for individuals who use public health services.

- NDIS participants from CALD backgrounds can access a free interpreter service when using the services and supports of NDIS registered providers.

- NSW Multicultural Health Communication Service is a state-wide service, providing a database of multilingual health information and health promotion activities. They also provide translation services.

Services for people from CALD communities

- The Ethnic Community Services Co-operative provides:

- NDIS services and resources

- advocacy

- volunteer projects for people with disability

- support for people with disability looking for work experience and paid employment.

- The Multicultural Disability Advocacy Association provides advocacy support for people with disabilities from CALD communities and those from non-English speaking backgrounds.

- Open Minds has support services for people from CALD communities with mental health problems.

- Action on Disability within Ethnic Communities has a range of services and resources including:

- advocacy support

- videos about the NDIS in different languages

- social support groups.

- Kin provides advocacy support for people with disability from CALD communities.

- The Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia has a Community Connectors program that supports people from CALD backgrounds to access the NDIS.

- Lifeline offers interpreters as part of their services. They can be contacted on 13 11 14.

Translated resources for people from CALD communities

-

Health professionals and others working with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities can use Health Translations to easily find translated health information in over 100 languages. The directory is an online library that provides web links to third-party sites with translated health and wellbeing resources. Those sites include government departments, peak health bodies, hospitals, and community health and welfare agencies. You can search for resources by language, topic, organisation, keyword and file type. This initiative is supported by the Victorian Government and managed by the Centre for Culture, Ethnicity and Health.

- Amparo Advocacy Inc has information on the rights of NDIS participants.

- The Cerebral Palsy Alliance provides some translated information and resources.

- Carer Gateway has information for carers and support networks in different languages.

- Centrelink information about the Disability Support Pension has been translated into a range of different languages.

- UnitingSA has translated fact sheets to help CALD communities to access the NDIS.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Cultural Competence in Health: A guide for policy, partnerships and participation. Canberra: 2016.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Cultural and Linguistic Characteristics of People Using Mental Health Services and Prescription Medications. Canberra: ABS; 2016. Contract No.: ABS Cat. No. 4329.0.00.001.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. User Guide for Health Service Organisations Providing Care for Patients from Migrant and Refugee Backgrounds. Sydney, 2021.

- Grant J, Parry Y, Guerin P. An investigation of culturally competent terminology in healthcare policy finds ambiguity and lack of definition. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2013;37(3):250-6.

- El-Amouri S, O’Neill S. Supporting cross-cultural communication and culturally competent care in the linguistically and culturally diverse hospital settings of UAE. Contemporary Nurse. 2011;39(2):240-55.

- O'Toole G. Communication-eBook: Core Interpersonal Skills for Health Professionals: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2016.